Finding Lost Voices: The Fortitude of Fanny Quigley (1870-1944)

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

This week marks the twenty-second week I’ve written Finding Lost Voices. Over the last twenty-two weeks, I’ve brought you the stories of novelists, poets, explorers, photographers, and so much more. If you missed any posts, you can find an archive below:

Elizabeth Stoddard and the Novel You Want to Read Right Now, The Morgesons

The Mysterious H.H. (Helen Hunt Jackson) who didn't want to leave a trace

Literary Community, Edna St. Vincent Millay and the "Poetess of Kansas"

The poet Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Baamewaawaagizhigokwe) and what she gave Longfellow

The Poet at the Hearth Tending to the Truth, the novels of Janet Lewis

"I demand you write more shamelessly and nakedly” --Meridel Le Sueur and her 1930s novel, The Girl

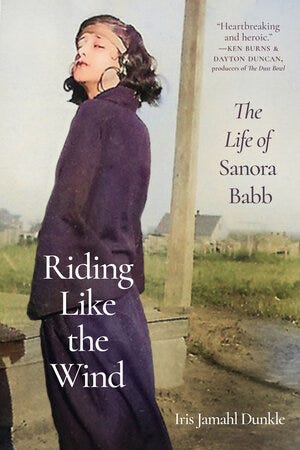

What Sanora Babb Heard in the Voice of Edna St. Vincent Millay

Finding Lola Ridge on the Lower East Side with Terese Svoboda

A Conversation with Author and Podcaster of Unruly Figures, Valorie Clark

In a Lonely Place, A Crime Noir classic by Dorothy B. Hughes

The Haunting Photos of Hansel Mieth Tell Us Truths We May Not Want to See

Jessamyn West Who Loved and Supported the "Muscular Activity of Writing"

Inspiration in the Archives of the Morgan Library and the New York Public Library

Writing this blog has been an incredible journey. One that I hope to continue. If you support my work and haven’t paid to subscribe, I hope you’ll consider doing so now.

This week, I wanted to return to a place I visited several years ago: Kantishna County, where the Denali National Park road ends near the foot of Denali. There, I was introduced to the life of an extraordinary woman: Fanny Quigley (1870-1944). Fanny lived in the rugged, isolated Kantishna County from 1905 to her death in 1944. By the time she died, she had become an Alaskan legend known for her rugged individualism, which defied gender norms. Her skilled hunting of large game and her wilderness cooking, including a blueberry pie made from rendered bear lard from bears, she hunted herself.

Quigley was born on a Bohemian homestead in Wahoo, Nebraska, where she learned to live off the land early. Like Sanora Babb, she was raised in a dugout. Between 1886 and 1889, the Burlington Railroad began to lay tracks through Saunders County where Quigley lived, and to add income to her family she took a job as a waitress in a mess hall serving railroad workers. Quigley likedthe railroad workers she worked with, and when the railroad work was complete in her area, she left her home and to follow the railroad work. It was the first in many descisions tht would lead her toward adventure. Quigley was nearly illiterate when she left, but by the time she’d worked for the railroad for almost a decade, she learned to speak English (laced with curse words) from the Irish railroad workers she associated with.

In 1898, word of the Klondike Goldrush spread south to where Quigley worked, and like thousands of others, she set out toward the prospect of fortune. The legends of gold attracted her, but Quigley was clever and set out to the Klondike to set up a mess hall where hungry miners could spend their newly found wealth. When new claims were found, she’d set out not with a shovel or a pan but with a cook stove and provisions to feed the hungry miners. In the Klondike, Quigley met Angus McKenzie and married him on October 1, 1900. The two operated a roadhouse near Hunker Creek. But Angus was a drunk who beat Quigley, so after a few years, she left him.

Quigley followed the rush for gold, walking to Tanana and then to Kantishna where she staked 26 claims between 1907 and 1919. Quigley married her second husband, Joe Quigley, in 1918, and they ran a mining operation together, leasing out their claims to miners. Their cabin, located en route to the base of Denali, was often visited, supposedly even by the writer Jack London.

But though it was mining that led Quigley to Kantishna, the beauty of Denali made her stay. Denali stands 20, 320 feet high, nearly 200 miles above the valley floor. When I visited Alaska, it loomed on the horizon like a beautiful beacon, always fading in and out a cloak of clouds.

We were clothed in mosquito nets, head to toe, the day we toured Quigley’s cabin. It was early June, and the mosquitos had hatched from the melting permafrost in droves. Since her death, the park service has restored the cabin and decorated it with artifacts like the ones she used. As we walked through, our tour guide explained what life had been like for Quigley. How she gathered wild food, hunted game, tended a massive garden (above tree line), and cooked the best blueberry pie anyone had ever tasted. But also how she mined and leased mines. How she was a naturalist and nurse. Quigley is the kind of Western woman we need to learn more about. The kind usually dismissed as an archetype: an old crone. The truth is that Quigley was adaptable and had immense fortitude to survive winters in a place where (before the roads) you had to drive a dog sled 100 miles to purchase supplies once a year. When we left our tour, I was haunted by Quigley’s story, and it followed me, as large as Denali itself ever since.

This looks amazing---such an important subject!

What a fascinating woman!