Finding Lost Voices: A Conversation with Author and Podcaster of Unruly Figures, Valorie Clark

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

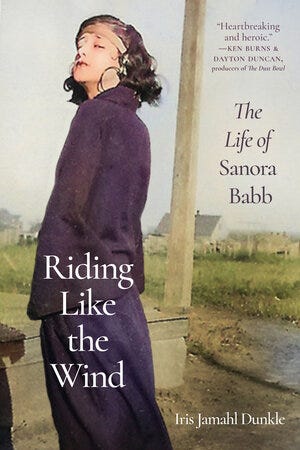

This week, I will feature a podcast and book doing the hard work of recovering and telling women’s stories. A few weeks ago, while I was at Millay Arts in upstate New York finishing my biography on Sanora Babb, I met another biographer and historian, Valorie Clark. Clark sat down with me recently to discuss her thriving podcast, Unruly Figures, and her new book of the same title just released in March.

Iris:

How do you find content for your episodes? Where do you encounter unruly figures?

Valorie:

Oh, that's a great question. I often encounter unruly figures in the footnotes of other biographies. For instance, I did a recent episode on Mary Carleton (1642 - 1673), who was known as the German Princess, you might have heard of her, and I found out about her because she is just mentioned in passing in Janet Todd's biography of Aphra Behn. I, of course, wrote a chapter about Aphra Behn (1640 -1689) in my book, but I had never heard of Mary Carleton because it would never have occurred to Google, “con woman using German heiress scheme in Restoration England.” Like, that's such a wild thing just to go searching for. But yes, she was a footnote, just a passing mention in another biography. And that's how I found her.

Iris:

When did the idea of creating your book, Unruly Figures from your podcast, begin? And how did it come into existence? And how long did it take you to write from start to finish?

Valorie:

Do you know what? I hit the jackpot. The second episode of the podcast went modestly viral, and an editor at my publishing house happened to hear the episode. She liked my voice and the way I was telling the story. So, she slid into my DMs, as the kids say, and asked if I wanted to write a book, and I was like, Heck yeah, I do. And so yes, after episode three or four, she contacted me, and we started writing it the following spring. From the contract to the day I turned in my manuscript was about seven months, but I only spent about three months of solid, dedicated work on it, which is not a lot.

Iris:

That's amazing. It takes me four to six years to write a biography. I'm so impressed.

Valorie:

Yes. I mean, the fortunate thing about this is that the biographies in my book are really short. So, I didn't need to know where they were every single day of their lives to figure it out. And the theme was narrow. For example, with Jonas Salk, there is so much information out there about him. You could easily write a 1000-page biography. My biography about him is only eight pages long. I just focus on the flu vaccine and polio and how he made these huge scientific advancements while passing off all his colleagues.

Iris:

In your introduction to your book, you mentioned that you fell in love with even the “whitewashed history” that you learned in Texas Public Schools. I'm wondering what year you were learning this history. And can you tell us when what you were learning shifted? I had the same experience growing up in rural California, where I learned about history and was told that all the Indigenous people of California had been killed off while I was sitting next to someone who is of Pomo-Coast Miwok descent. So, I immediately distrusted history, and I wonder if you had that same experience and what drew you to creating this podcast.

Valorie:

I graduated from high school in 2008, so I was learning history during the early 2000s and late 90s. From a young age, I knew that the history we were being taught was simplified thanks to a teacher who complained; how do you want me to explain 10,000 years of human achievement to 7th graders in 1 year? But actually, what got me was realizing that some of the history I had been taught was not just simplified but outright wrong. Or even an outright lie. When I was in college, a girl I knew just informed us that she had been diagnosed with an STD, and we were all horrified. We were like, Oh my God. How are you going to survive this? And she responded, What are you talking about? You take penicillin, and you're fine. I'm not going to die from this, which is what I was taught in school. It was very much like the Mean Girls scene where they're like, you have sex, you'll get pregnant and die. Or you have sex, you get an STD, and you die, and when I learned that that was not, in fact, the case, then I began to doubt everything that I had been taught about history. It took one lie to shatter the whole illusion of historical accuracy.

Iris:

Well, it's clear by how you write about these characters that you're deeply invested in telling their stories. So why are you so drawn to these unruly characters?

Valorie:

It's funny. I think one of the things that I've kind of come to a conclusion about after the last 2 1/2 years that I’ve been doing the Unruly Figures podcast is that this urge to rebel might be one of the few things all humans have in common. Across all societies. All humans feel hunger, they feel sleepy, they feel love, they feel lonely. But we also share that there will always be a button you can press that will make almost any human finally break and start a revolution. Whether they'll be successful at that revolt is a different conversation. Still, it's a universal experience that I think people tend to present as being unique, that revolutions are rare and difficult. And that it takes a particular person to do it. But it isn’t rare or unique. Anybody could rebel; oftentimes, it's just anybody who finally stands up and does.

Iris:

I'm wondering. Do you think it's different for women? Do they have to be unruly to be seen or remembered during some of these eras?

Valorie:

I think, unfortunately, because of the way history was written by men, about men, and for men for women to be remembered, they did often have to break the rules. If you listen to the podcast a lot of times, you’ll notice I'll launch into a story about a woman in her teens or early twenties, and I have to state we have no idea what she was doing before this because no one bothered to record it; she was just a girl, and no one cared. Whereas, even in the 1500s, we know what (Western European) men were doing up from when they were young. Unfortunately, it is the case that when your historical narrative is controlled by one group of people, you have to stand up against those people and risk being branded as some criminal to be noticed.

Iris:

Reading your book, I was struck by the fact that the only female unruly figure I was acquainted with before reading your book was Aphra Behn. Thanks for introducing me to so many other fascinating women! Who is your favorite female unruly figure, and why?

Valorie:

Man, oh, that's hard. I have a special affinity for Joe Carstairs (1900 - 1993), who did whatever she wanted and didn't worry about it. Manuela Saenz (1797 - 1856) is a cool story. But she was very worried about politics and the visibility of her lover, Simone Bolivar, whereas Joe Carters just wanted to live her life. Her life was remarkable; she just did it quietly and didn't care what other people thought. And I love her for that.

Iris:

Can you tell those of my readers who haven't yet read your book, Unruly Figures, a little bit more about her?

Valorie:

Yes. Joe Carstairs was born in 1900 and was the only daughter of a wealthy family. She was an heir, twice over on both sides. Her mom kept getting remarried over and over again. Joe never had good relationships with her stepfathers until her fourth one, I believe, who taught her how to race cars and how to smoke a cigar and took her to strip clubs when she was like fourteen. And after that, she decided that that was the life she wanted for herself. She drove ambulances during World War One when she was only 16. She, of course, inherited a lot of money from her family, but then she also kept winning all these races and getting more money, and she helped streamline the way motorboat races were done at the time. And she threw these wild, raucous parties in London with her lover, Ruth Baldwin (1905 - 1937). Then, one day, she just decided she was fed up. It was in the late 1920s/ early thirties. Once they grew up, the boys who were too young to go to war during World War One pushed back on this newly freed woman of the early 1920s. And so, women like Joe were really, really reviled suddenly in a society that had previously celebrated them and their efforts during the war. And so, she was like, OK. I'm out of here. I'm going to take my money and buy an island in the Caribbean, and I'm going to pay Caribbean native workers better than the British did on plantations. Because she paid the native workers so much better and treated them well (even establishing an early health insurance program), she could steal all their workers and develop the island. Then, she just moved to Florida when she was ready to retire. Yes, she was cool.

Iris:

Oh wow, that's amazing. So, who is your favorite female unruly figure who didn't make it into the book? You mention in the afterword how it was impossible to narrow it down to just these twenty figures that you cover in the book and how there are so many other stories orbiting around them. So, who didn't make it into the book you've covered in your podcast that you also like?

Valorie:

Oh, I mean. Mary Carlton didn't make it into the book. But I covered her in the podcast, and she's excellent. She's so fun. Christabel Pankhurst (1880 - 1958) also, I think, would have been fascinating. She was. working and living in the UK and advocating for women's rights to vote, she led the more militant wing of those protests. She was connected to the bomb at Westminster. Before her, people had tried to get women the right to vote for decades through peaceful methods. Methods that were not working. Christabel Pankhurst was like, no, no, that's not working. Let's go crazy, and after they get the right to vote, in a total break with her past, she moved to the US to become an evangelical preacher later in life. She was an exciting story, but she didn't make it into the podcast or the book because I had already covered another suffragist, Mary Maloney (1878 - 1921).

Iris:

Mary Maloney's story was fascinating, too. So now that you've started a podcast. And now you've written a book. What project do you intend to take on next?

Valorie:

At Millay Arts, where we met, I just finished the first draft of my historical fiction novel, which may be standalone or evolve into a trilogy because it's set in this period in history when there are these three different women leading. Two women are leading official wars, and the third character that I wrote about is leading an individual revenge campaign on the high seas between England and France. It would be cool to focus on that creative work for the next few years. And I would also love to write a second sequel to my book, Unruly Figures.

Iris:

Wonderful. So, just as a final question, I wanted to ask you what do we gain by telling the stories of unruly figures.

Valorie:

Man, that's a good question. I think what we gain is twofold. First, we gain a more realistic view of history. Often, history is told as if it’s a peaceful transition until we get to these sudden wars that explode out of nowhere, which is just not how it is. Even today you constantly see articles that state America has never been so divided, which isn’t true. People have always been this divided as everyone has always disagreed about the best way to live. Civil wars erupt over it. And that happens more often than we're taught in school. Those civil wars were led by people, by rebels who wanted a different life. Second, we get examples of how to be brave enough to live outside the rules prescribed to us. Whatever that rule is, and whoever is prescribing it, telling these stories gives people a way to see themselves as people who could walk away from a system that doesn't work for them.

Iris:

Thank you so much for joining me today! Readers, you don’t want to miss Valorie’s podcast, Unruly Figures, her substack, and her book!

Upcoming Events

Saturday, April 13, 2-7:30 PM Lit Crawl Sebastopol - 3:30 PM at The Redwood (234 South Main St., Sebastopol)

MFA PROGRAM CREATIVE WRITERS of Dominican University of California: JOAN BARANOW, MARY STEPHENS, ROBERT F. BRADFORD, CATHARINE CLARK-SAYLES, NICHOLE TURNBLOOM, TURNBLOOM IRIS JAMAHL DUNKLE

April 20, 2024, 10:00 AM - SUITE 300A, NEW ORLEANS HEALING CENTER, 2372 ST CLAUDE AVE (New Orleans Poetry Festival) Marcela Sulak, Charlotte Pence , Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Sarah Rose Nordgren, Nicole Callihan and Danielle Pieratti