Finding Lost Voices: Jessamyn West Who Loved and Supported the "Muscular Activity of Writing"

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

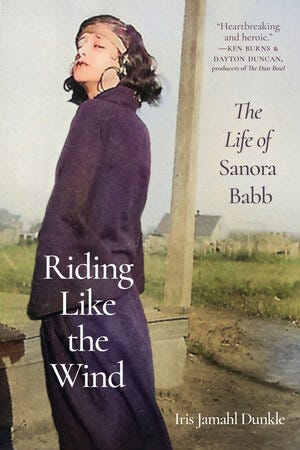

Every year at Napa Valley College, there is a creative writing contest called The Jessamyn West Writing Contest. The event is always a special day because it’s at the awards ceremony that we get to honor our creative writing students. For a long time, all I knew about the author, Jessamyn West (1902 - 1984), after whom the award is named, was that she had lived in Napa, she was married to our first school president, Harry McPherson, and had a successful career as a writer. But, over the last five years, as I’ve spent time researching the life of her contemporary, the author Sanora Babb, I’ve learned much more about what a substantial writer she was.

West was born in North Vernon, Indiana, to a family with Quaker roots, but her family moved to Yorba Linda, California, when she was six. West’s mother was a cousin to Richard Nixon’s mother, and West often babysat Richard when he was a child (later, she became a close and lifelong friend of the future president, sometimes even traveling with the presidential entourage.) She got her teaching credential at Whittier College, and shortly after graduation in 1923, she married McPherson. The two moved to Hemet, CA, where she worked as a local reporter and then as a school secretary. Later, she would work as a schoolteacher in a one-room schoolhouse, teaching all eight grades in the same room.

But, West wasn’t satisfied and longed to learn more. In 1929, she left teaching to complete a summer program at Oxford University. While she was overseas, she visited Paris where she discovered the famous bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. The shop had released James Joyces’ controversial novel, Ulysses in February 1922 and West bought a copy. She was immediately pulled in. Here was an author who muscled his way through his art, who wasn’t afraid to write what critics found obscene. At the time, Ulysses was still illegal to bring back to the United States. West didn’t care. To get the book through customs, she hid it in her suitcase under jars of marmalade.

When West returned to the United States, she was determined to pursue a higher degree in literature. She enrolled in the Ph.D. program at UC Berkley and had nearly completed her degree when disaster struck. Just before taking her doctoral orals, West suffered a severe lung hemorrhage and was diagnosed as having an advanced case of tuberculosis. In August 1932, she entered La Viña Sanatorium near Los Angeles as a terminal patient. (West would write about her experiences in the sanatorium in her 1976 memoir, The Woman Said Yes: Encounters with Life and Death). During her stay, West would become so ill that the doctors encouraged her family to bring her home so that she could "die amongst her loved ones." However, after several years of treatment, in 1934, she overcame the disease, and she was able to leave the sanitarium to recover at home.

Most biographies begin West’s writing career at this point. Telling us she became inspired while living in the sanitarium and discovered writing as a means of coping with isolation and sickness. But in other interviews, West admits she’d wanted to be a writer from a very young age. She just hadn’t told anyone about this desire. Growing up, West had never encountered a writer, so she had no idea that she could choose to become one.

“I like marking the signs that stand for words on a page. I like the look of it. I’m not a person who wants to crochet or peel a carrot. There’s other work I do, but I prefer it to be big muscle work. I want to sweep and scrub. But writing . . . just the muscular physical activity of writing, I love.” Paris Review Issue 71, 1977

When she was West was just fourteen, her parents gave her a scrapbook to document her memories. Instead of filling it with photographs of her friends like most girls her age, however, West filled the scrapbook with plots for stories she’d write in great detail. Plots that she would later go back and assess and edit, writing “NUTS” or descent” across the tops of pages. West also was the Editor-in-chief of the literary magazine, Pleiades, in high school.

West claimed her love for writing was drawn from her profound love of reading. “I go to sleep reading, and I wake up reading. Somehow, I have the feeling that in some book is the great treasure I’ve been looking for all my life.”

But it wasn’t until West left the sanitarium and began what she’d call her “ten horizontal years” recovering from tuberculosis at home, that she started writing with the intent to publish. While she recovered, her mother had told her stories about her life growing up in rural Indiana in a Quaker family. The stories and her near death experience inspired West to pursue the life she’d always dreamed of: the life of a writer. As West would later tell an interviewer reflecting on that time: "I thought my life was over," she said of those hopeless days. "Instead, for me, it was the beginning of my life."

Submitting her work and finding success first in little magazines like New Mexico Quarterly and Prairie Schooner. When West received her first letter from an editor accepting her work, she slept with it under her pillow and looked at it every morning when she woke up. Then later, her work was published in popular magazines like Harper’s, Mademoiselle, Kenyon Review, The New Yorker, and Redbook and was included in many of the Best Short Story collections (alongside Sanora Babb and her contemporaries), and she gained a national readership. West’s first and most famous collection was published in 1945: The Friendly Persuasion, which collected fourteen vignettes about a Quaker family living near Vernon, Indiana, during the Civil War. Many of the stories were based on stories West’s mother had told her about her own experiences and the experiences of West’s grandmother. It was essential to West that the Birdwell family, whom she depicts in the book, were presented as characters "who happened to be Quaker" rather than just as personifications of Quaker traits.

The novel drew the attention of Hollywood and was adapted into the 1956 academy-award-winning movie Friendly Persuasion, starring Gary Cooper and directed by William Wyler. West got to write the screenplay and wrote about her experience in her memoir To See the Dream (1959). Except for Me and Thee, the sequel to The Friendly Persuasion was adapted into a 1975 television movie titled Friendly Persuasion.

West would continue to have a long, and successful career. Her published novels include: The Witch Diggers (1951), Cress Delahanty (1953), Little Men (1954), South of Angels (1960), A Matter of Time (1966), Leafy Rivers (1967), Except For Me and Thee (1969), and The Massacre at Fall Creek (1975). Volumes of short stories include: Love, Death and the Ladies Drill Team (1955), Crimson Ramblers of the World, Farewell (1970), and The Woman Said Yes (1976). Nonfiction works include: The Reading Public (1952) and Love Is Not What You Think (1959). She even wrote a book of poetry, called, The Secret Look (1974), and an opera libretto based on the life of Audubon called, A Mirror for the Sky (1948).

West died in 1984. She was remembered by Jacqueline Koenig as someone who "accomplished things when she'd never actually known anyone else who did them. She must have been fearless. In her life and her work, she perfected a combination of intelligence, toughness, determination, compassion, talent, beauty, kindness, and love that is inspirational. She truly lived the life she really wanted."

Next Monday, we will hold our next award ceremony to honor the undergraduate writers who have won the Jessamyn West Writing Awards. As I stand at the podium with my colleague, introducing our winners, I will do so remembering the important writing career of the woman who made these awards possible, Jessamyn West. Perhaps not only the award, but also the life she lived will inspire the award winners, to live the life they want.

Want to Learn More about Jessamyn West?

Read Jessamyn West, The Art of Fiction No. 67 in The Paris Review

Listen to Sherman Alexie read "The Lesson," by Jessamyn West.

Wow, Iris. These bulletin/bios are truly marvelous and inspiring. Thank you.

she lived in napa Valley and her adopted daughter still lives here. She and her husband had a big influence here