Finding Lost Voices: The Mysterious H.H. (Helen Hunt Jackson) who didn't want to leave a trace.

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

As I write this post, I’m sitting in a room stuffed to the brim with poetry collections and folders filled with the work and lives of women writers at the Sitting Room, in Pengrove, CA. The rain is drumming down on the roof but otherwise, the house is still and quiet, except for the voices of so many women writers I can’t wait to tell you about. (I’ll go into more detail about The Sitting Room Library in a future post.) This place has been a haven for me since my children were young and I needed a quiet space to retreat to in which to write. That’s why it feels so right, spending time here now to write about another woman writer you haven’t heard enough about. It’s time to amplify those voices I hear whispering from the shelves.

Helen Hunt Jackson (1830 - 1885) was incredibly famous during her lifetime. So much so that when she died in August 1885, The Nation wrote that the news of her death would “carry a pang of regret into more American homes than similar intelligence in regard to any other woman with the possible exception of Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe.” So if Helen Hunt Jackson was that popular at the time of her death, what happened over the ensuing decades to wash away her image from our collective minds?

She was born Helen Maria Fiske in Amherst, Massachusetts, the daughter of Nathan Welby Fiske and Deborah Waterman Vinal Fiske. Her father was a minister, author, and professor of Latin, Greek, and philosophy at Amherst College. She had two brothers who died soon after birth, and one surviving sister, Anne. Her parents were strict Calvinists; ideas Helen Hunt Jackson rebelled against in her poetry. During her childhood, she and Emily Dickinson played together occasionally.

Tragedy struck Helen hard at a young age and continued to ring its dull bell. Her mother died from tuberculosis in 1844, when she was fourteen. Three years later, her father died. Luckily, he had provided financially for her education at Ipswich Female Seminary and the Abbott Institute, a boarding school in New York City run by Reverend John Stevens Cabot Abbott (where Lavinia Dickinson - Emily’s sister - also attended).

Helen married Edward Hunt in 1852. The couple traveled a great deal as he was in the military (she called their lifestyle: scaterdom). In 1855 they moved to Rhode Island where she began to establish her literary career through the salons of Anne Lynch Botta. Then, her husband was killed in a military accident at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Helen had two sons with Hunt; however, neither son lived to see adulthood. One died as an infant from a brain tumor. Her other son Rennie, died in her arms at nine years old. Rennie’s death was a devastating blow to Helen from which she would never entirely recover. In 1882 she recalled his death and the depth of her sorrow in a letter to an acquaintance, “My boy would be a man now—twenty-seven years old. But every moment of that night is as vivid to me as if it were yesterday. I shall never be so old that I can think of it or of him without tears.”

In her grief, Helen Hunt Jackson turned to writing. Her first publication, a poem titled “The Key of the Casket,” appeared in the New York Evening Post on June 7, 1865, less than two months following Rennie’s death. From this time forward, she devoted herself entirely to forging a literary career. By the 1870s, Ralph Waldo Emerson named her the best contemporary woman poet.

“I never write for money. I write for love, then after it is written I print for money….Cash is a vile article – but there is one thing viler; and that is a purse without any cash in it.” –Helen Hunt Jackson to James Fields

Over the next two years, Helen published three novels in the anonymous No Name Series, including Mercy Philbrick's Choice (1886) and Hetty's Strange History (1877). She urged her friend, Emily Dickinson to submit poems anonymously to A Masque of Poets, part of the same series. Soon, Helen was able to completely support herself with her writing.

In the late 1800s, tuberculosis was thought to be hereditary. Ever since her mother had died of the disease, Helen had been terrified that she too would succumb to it. In the winter of 1873–1874 when she began to show symptoms, Helen immediately traveled to Colorado Springs, Colorado to stay at the Seven Falls resort. And it’s there in the clean, cold air of Colorado that Helen met her second husband, a railroad executive named William Sharpless Jackson. She fell in love, but she wasn’t about to give up her writing career. Before they were to marry he had to agree to not interfere with her writing. He did and they married in 1875.

While living out west, Helen became deeply angered at the plight of indigenous people and began writing about the topic. In 1879, she attended a lecture by Chief Standing Bear, of the Ponca people. Chief Standing Bear described the horrors his community faced during their forcible removal from their Nebraska reservation and transfer to the Quapaw Reservation in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Helen was so moved by his speech she felt called into action. In response, she wrote the first book she would publish under her name, A Century of Dishonor (1881). A book that was an unvarnished report of the US government’s long-standing betrayal of Indigenous people and where she called for significant reform in government policy. Helen sent a specialized copy of her book to every member of Congress that had a quote from Benjamin Franklin printed in red on the cover: "Look upon your hands: they are stained with the blood of your relations."

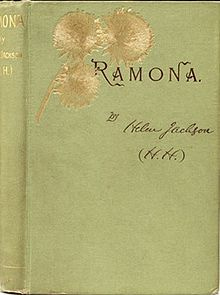

Helen traveled to Southern California where she spent time researching her next novel. A novel that would catapult her to incredible fame: the bestselling romance Ramona (1884). Ramona is set in Southern California just after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the annexation of the territory by the United States. The book tells the story of a mixed-race Scottish–Native American orphan girl named Ramona who was raised on her aunt Señora Moreno’s rancho. Ramona falls in love with Alessandro Assis, a young Native American sheepherder who is working on her aunt’s ranch and they run away together. Their quest to find a home where they can raise a family without facing prejudice is what constitutes the second half of the book. While Helen greatly romanticizes the mission system, she shows in sharp detail the cruelty indigenous people faced as the Americans moved in and stole their land.

“I did not write Ramona; it was written through me. My like-blood went into it.” –Helen Hunt Jackson

But even though Ramona was incredibly popular, the book didn’t do the work Helen had intended. Most readers saw it as a tender love story. While she’d sought to portray the indigenous experience "in a way to move people's hearts" to action the same way she had been called to action at Chief Standing Bear’s speech,

as Harriet Beecher Stowe had done for enslaved African Americans in her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Beginning in the 1930s a play based on Ramona has been running at the Ramona Bowl in Hemet, CA now for 101 seasons.

So the question remains, why do we not remember Helen Hunt Jackson nearly 150 years after her death? Part of the reason is because Helen distrusted the way her story would be told. She wasn’t a conventional woman of her time. She was outgoing, driven, and not one to hold her tongue. She burned most of her letters. She rarely gave interviews during her lifetime. And, she published most of her work anonymously or under pseudonyms. To find her story, you have to look away from the standard story. You have to dig in the cracks and piece together her life. Thankfully, Kate Phillips has done this hard work in her biography, Helen Hunt Jackson: A Literary Life.

Next week, I’ll be bringing you an interview with the feminist, indie press, Cita Press.

What to hear me read from my work? Catch one of my upcoming February readings.

2/2 6:00 PM PST at Readers’ Books, Sonoma, CA with poets Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Nicole Callihan, and Gillian Conoley who will read from their work.

2/7 6-8 PM CST Wild Patience: Readings by Poet Moms, 21 C Museum Hotel 219 W. 9th St.Kansas City, MO

2/7 8-10:30 PM CST Wednesday Night Poetry Live Charlotte Street Foundation 3333 Wyoming, Kansas City, MO

2/8 2:00 PM PST I Aim to Misbehave: Annie Oakley and Other Defiant Historical Women -Virtual - The virtual launch of LADY WING SHOT by Sara Moore Wagner with Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Caroline Plasket and Rikki Santer.

2/8 5-7 PM CST Braving the Body Anthology Launch Cheval on Main, 3940 Main St.Kansas City, MO

2/15 7:00 PM at John Natsoulas Gallery, Davis, CA with poets Iris Jamahl Dunkle and Cami Rothmuller

2/17 5:00 PM at Jessel Gallery, Napa, CA with LENORE HIRSCH, MARY HOLMAN TUTEUR, IRIS JAMAHL DUNKLE, PAUL WAGNER

Iris, this is fascinating! Sometime, you and I should talk about Helen Hunt Jackson's competition with Neith Boyce.