Finding Lost Voices: "I demand you write more shamelessly and nakedly” --Meridel Le Sueur and her 1930s novel, The Girl

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

I recently visited the Deborah Butterfield exhibit, P.S. These Are Not Horses at the Manetti Shrem Museum at UC Davis with my creative writing students. When we walked in, we were overwhelmed. The sculptures were of abstract representations of horses made of mud and sticks, made of bronze, made of bronze treated to look like burnt wood. Within minutes we were almost all sitting on the floor, scribbling in our notebooks, having conversations between ourselves and the objects Butterfield had so beautifully crafted.

One sculpture, in particular, caught my attention. I kept returning to it. Every time I’d walk through the musuem, it would call me back. Titled, Uha’Ula’Ula, the horse, made of scrap steel, looks like it is falling or rising. As soon as you see the horse you can tell she is female; something about the language of her body tells you. The horse reminded me of my mother, of my grandmother, of all of the women in my life who’ve had to fight to get back up, fight to be seen, the collective trauma we’ve suffered, are suffering, and will continue to suffer as women. And sitting there on the musuem floor next to the weight of the sculpture felt like a conversation, a place between generations where this grief could be shared and re-membered.

I’m in copy edits right now, finalizing my next biography, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb, a book I’ve poured my whole heart into. Copy edits are tough because they are your last chance as a biographer to get everything right about telling the story of a life, a pressure that’s compounded when the life you are writing about has been misremembered or forgotten. Part of the copy-editing process is going back through every source I’ve cited and verifying it. While I was going through one of my chapters, I was reminded of two letters Meridel Le Seuer wrote to Babb in the 1930s.

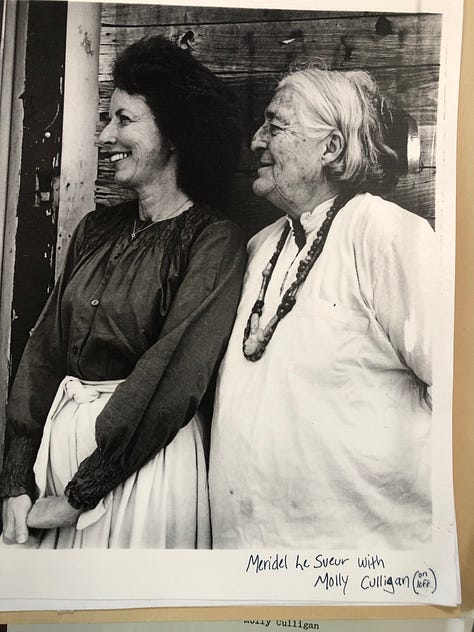

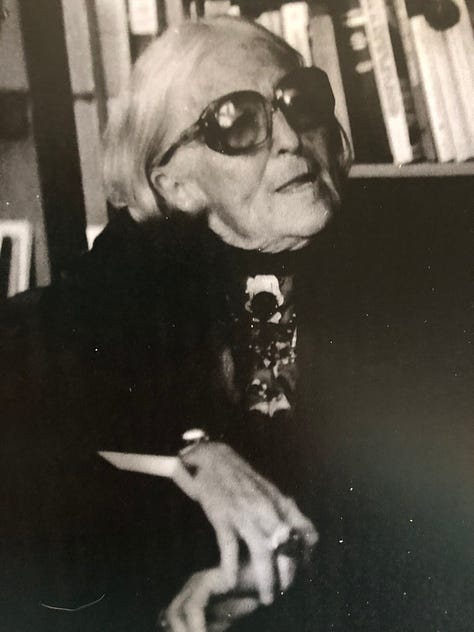

Meridel Le Sueur (1900 -1996) was raised by a feminist-socialist mother (Marian Wharton) who lectured on the Chautauqua circuit about topics such as birth control. Le Sueur grew up in the Midwest (Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas) before her family settled in Minnesota and became active in the Farmer-Labor Party. As an adult, Le Sueur switched parties and joined the communist party in the 1920s. During the Great Depression, Le Sueur divorced her first husband and lived in Minneapolis as a single mother raising her two daughters. She published her first story in The Dial in 1928 and continued to publish her work in mostly left-leaning publications, but even though she received substantial recognition; her work was praised by prominent writers such as Sinclair Lewis, Nelson Algren, and Carl Sandburg, she was unable to support her family off of her writing. The Workers Alliance offered support for unemployed, and underemployed people in the Twin Cities, and Le Sueur became deeply involved in this organization.

In 1935, when Le Sueur’s correspondence with Babb took place, Babb had also begun to publish her short stories and articles in leftist and communist publications and Le Sueur took notice. In her first letter, Le Sueur urged Babb to do two things.

First to attend the 1935 League of American Writers’ Congress in New York where Le Sueur would be the lone female among twenty-eight scheduled speakers. (Babb would go as a representative of the Los Angeles Chapter).

Second, Le Sueur urged Babb to continue to write “reportage” like her own “I Was Marching!” (1934). Le Sueur’s piece was inspired by the 1934 Teamster Truckers’ strike in Minneapolis.

“Reportage” is a reporting style that arrived in the U.S. via Europe and the Soviet Union. It was popularized by John Reed who used it to make the reader experience the event as the writer had experienced it, through sensory-rich imagery and other creative tools. Le Sueur was dedicated to reporting about the women she saw suffering around her. Through her reportage and fiction, Le Sueur became known as “the biographer of the ordinary” highlighting the domestic sphere and how events affected women and children.

Le Sueur saw Babb’s potential when she read her essay about the labor conditions at the Hoover Dam construction site in 1932. In the 1930s most of the major publications were stocked with male writers who wrote about the experiences of men. Le Sueur thought Babb could help her change that. She noted Babb’s use of strong female protagonists in her fiction.

“Well, what I am trying to say is that you must write now like a woman, give yourself your experiences as a woman and make a path” —Le Sueur to Babb

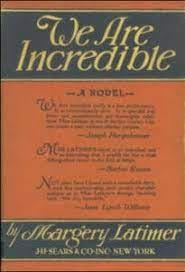

Le Sueur encouraged Babb to write about women, not only for herself but for all of the other women out there who were never represented in literature. She gave Babb a reading list, a lineage from which she could write and create a path for her work, including her own short story, “Corn Village” and the work of Margery Latimer. Latimer was known for her two highly acclaimed experimental novels, We Are Incredible (1928), and This is My Body (1930). [Don’t worry I’ll be writing a future post on Latimer! But until then, check out this episode from Lost Ladies of Lit about her.] Both of these books, though they were extremely popular during the 1930s (Latimer’s work was compared to Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and D.H. Lawrence by reviewers) are currently out of print.

Babb would take Le Sueur’s advice. After visiting the model farms in the Soviet Union in 1935, Babb would volunteer for the FSA working at the California camps that housed the refugees of the Dust Bowl in 1938. This work inspired Babb to finish her novel, Whose Names Are Unknown which offered a version of the Dust Bowl novel that also contained the lives of women and children. Babb’s second novel, The Lost Traveler about a young girl, whose father is a gambler like her own father, was unapologetically frank about her views about sexuality and independence for women.

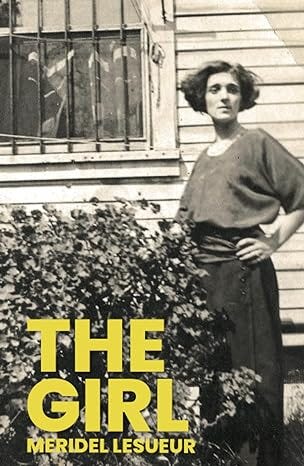

Le Sueur would also write a novel in 1939 called, The Girl, about an unnamed girl who arrives in St. Paul, Minnesota, and begins working as a waitress in a bar called, The German Tavern. There is bootleg liquor and gangsters and the book follows the girl through her pregnancy and eventual awakening to a different type of life thanks to the Workers Alliance (based on Le Sueur’s own experiences and the women she met there). The book begins with a birth and ends with a birth and in between the novel depicts women’s lives intimately: what it is like to have to care for others and the toll that has on the self. We see women who are hollowed out by violent marriages or dire circumstances. But we also see women rising from their range of circumstances. We meet a community of women who share in their collective trauma during the horrible circumstances of the depression.

The Girl would not be published when it was written due to its frank content about female sexuality. Additionally, the manuscript (and Le Sueur) was blacklisted during the McCarthy Era for its Communist ideas. West End Press would finally publish The Girl in 1978 and a new edition is now available.

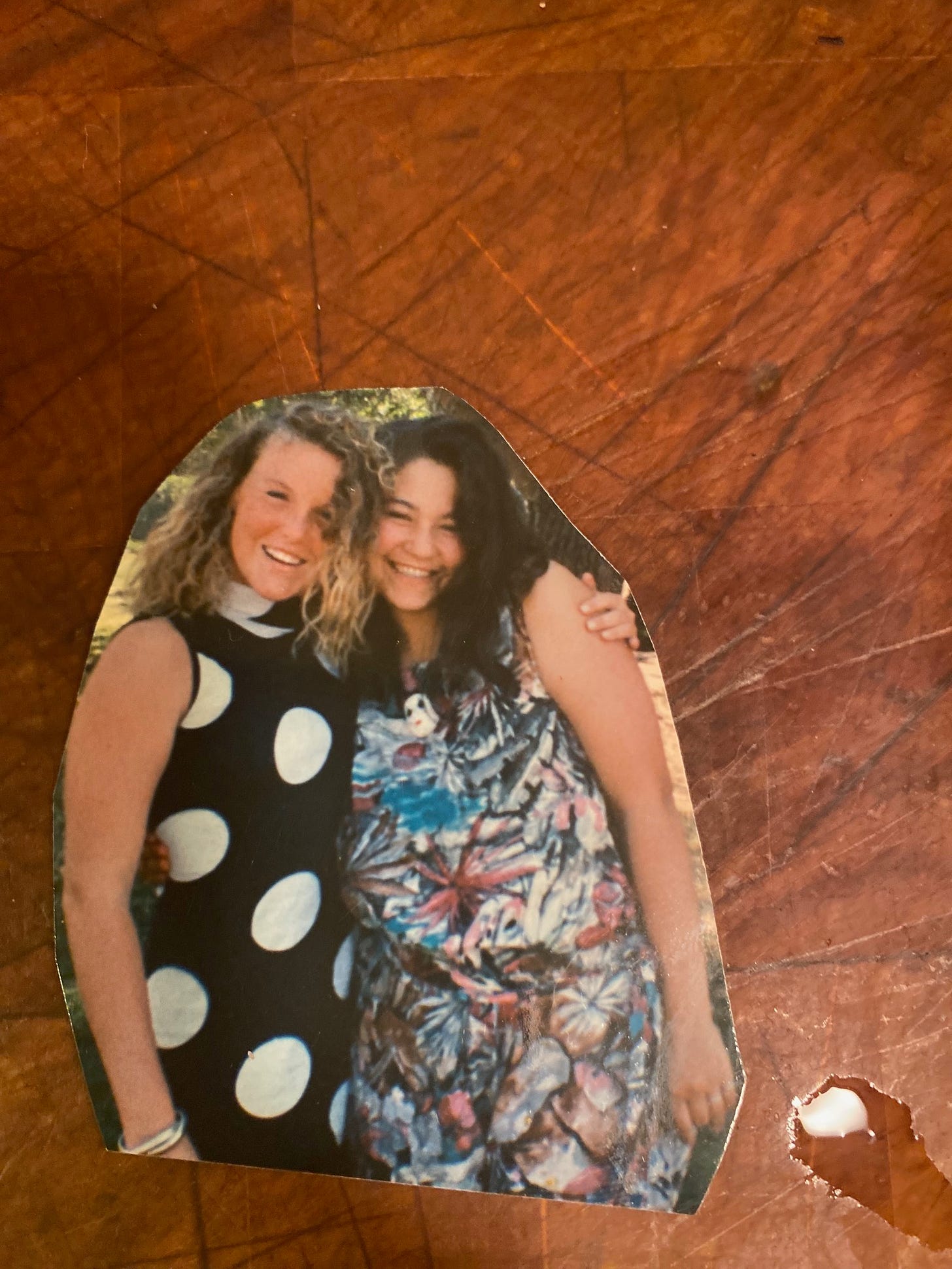

When I was sitting on the floor of the Manetti Shrem Musuem looking at Butterfield’s sculptures of horses or not horses it felt like she was speaking directly to me in the collective voice of what it means to be a woman in our world today. I could feel the trauma between us, like the horse, somewhere between rising and falling. Her creative impulse fed my own. It’s a voice I also hear in Le Sueur’s The Girl and in the letters, she wrote encouraging Babb to create art about women’s experiences. As it turns out, I could have found out about Meridel Le Sueur much earlier in my life. When I was interviewing Rebecca Anne Dahmani, Meridel Le Sueur’s great-granddaughter for my biography on Babb, she reminded me that we went to high school together. When I turn back to my copyedits, I do so reminded of the important role art plays in surviving our circumstances, in recovering the lost, and in knowing we are not alone.

To learn more about Meridel Le Sueur read my previous article “Meridel LeSueur: “Write More Shamelessly and Nakedly”

3/23 9:00 AM - 3:30 PM PST Workshop: The art of mini-biography and autobiography, or how to find the story of a life taught by Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Dominican University, Edgehill Mansion 75 Magnolia Avenue San Rafael, CA