Finding Lost Voices: "Time and Place Have Had Their Say" on Visiting Zora Neale Hurston's Grave

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

Welcome to the latest issue of Finding Lost Voices. Thank you to all who have become paid subscribers. I appreciate your support. If you’ve enjoyed these posts and have the means, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Last week, the sun beamed down the day I visited Fort Pierce, Florida, with my friend J.J. Wilson, the incredible Virginia Woolf scholar and founder of The Sitting Room. While on a book tour, I stayed with her at her home in Vero Beach on my way from Key West to New York. Before this, I was in Garden City, Kansas, a small town where the author, Sanora Babb, spent her early adulthood and set her first published novel, The Lost Traveler (1958). I gave a talk at Babb's alma mater, Garden City Community College. The audience was filled with locals, many of whom had only recently discovered Babb and her connection to their community. I was equally shocked to learn that none of Babb's books are taught at the schools in Garden City. To be disappeared is one thing, but to be erased from the place where you lived seems another thing entirely.

This local erasure reminded me of a moment in Alice Walker's famous essay about her journey to rediscover Zora Neale Hurston, "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston" originally published in Ms. Magazine in (1975), in which Walker asked a local woman whether or not Hurston's books were taught and read in the Eatonville, FL schools (where Hurston grew up), 'No, they don't." said the woman. "I don't think most people know anything about Zora Neale Hurston." Like Hurston, Babb's name is no longer known in her hometown. But many of the monuments from her time there still survive, including The Windsor Hotel, where her father spent much of his time gambling with marked cards.

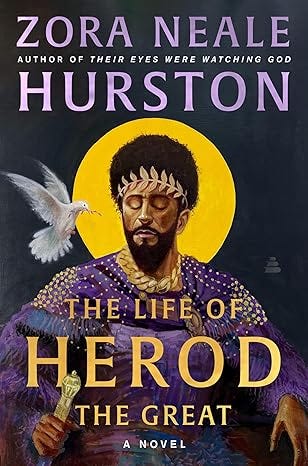

When J.J. and I visited Fort Pierce, FL, I had Walker's pilgrimage in mind. After leaving Eatonville, Walker continued her journey trying to find evidence of Hurston’s life to Fort Pierce, where she went searching for Hurston's final resting place. The city is located on the banks of the Indian River on the Florida Coast. J.J. drove me past Hurston's last home before her final illness struck her, a light green block house on School Court Street. It's in this house that Hurston worked on her last book, The Life of Harrod the Great (a book she considered to be her masterpiece). When a cleaning crew emptied Hurston's house after she died at the Lincoln Park Nursing Home, they threw the manuscript into a burn pile. Luckily, Patrick Duval, a deputy sheriff, noticed the fire in the backyard when he was driving past, and he swiftly put it out, salvaging much of the manuscript. Eventually, he donated the manuscript and other papers he salvaged to the University of Florida, Gainesville.

Thanks to Walker and many other scholars, Hurston's story was reclaimed, and she's likely a name you already know. Her story reminds us how important it is to care for our foremothers' history.

Zora Neale Hurston (1891 -1948) was born in Notasulga, Alabama, the fifth of eight children. She spent her early life in the all-black town of Eatonville, FL, where she attended the Hungerford Industrial and Normal School, a school founded on Booker T. Washington's principle that "all obstacles, including racism, could be overcome through the power of individual merit." (Zora Neale Hurston's Final Decade, 9). As a child, Hurston was an "imaginative, headstrong, rough-and-tumble tomboy with a passionate wanderlust" (11). When her mother died in 1904, and her father remarried a twenty-year-old woman five months later, all of the stability Hurston had known dissolved, and her life fell apart.

It wasn't until 1917 that she was able to continue her education at Morgan Academy in Baltimore, MD. She went on to study at Howard University, where she launched the school newspaper and published several short stories. She continued her studies at Barnard and then spent two years as a graduate student in anthropology at Columbia University. It was in Harlem that Hurston met fellow writers Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen, and she began publishing her creative work in places such as Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. Her work combined her incredible knowledge of anthropology with pristine literary craft. She would become one of the most critical voices of the Harlem Renaissance for her portrayal of racial struggles in the South. She published four novels (including Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), over 50 short stories, essays, plays, and an autobiography.

Hurston moved to Fort Pierce in 1957, where she worked at the local school. She went to jazz sessions at A.E. "Beanie" Backus's home. Backus was a celebrated Florida landscape artist who mentored artists from the Highwaymen like Alfred Hair. At jazz sessions in Backus's tin-roofed home, Hurston met with her journalist friends, Majorie Silver Alder and Ann Wilder.

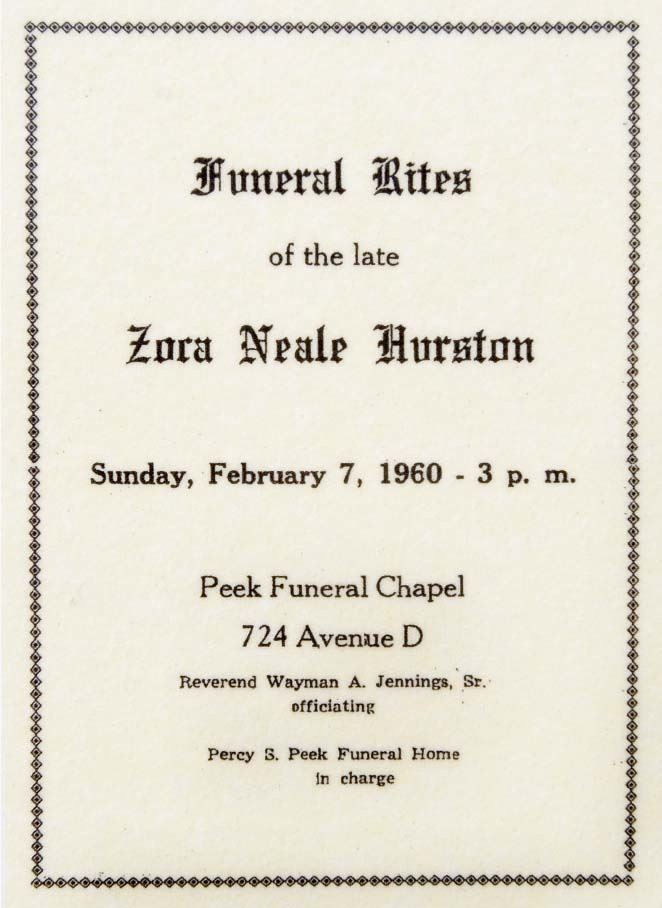

During this time, Hurston wrote for the Fort Pierce paper, the Chronicle. Then, in February 1958, Hurston worked as an English teacher at Lincoln Park Academy. Her students remember that instead of using a textbook, she'd incorporate "her grammar lessons with stories and fables about life." (155). After giving them assignments, she’d sit down at her desk and work. At the time her students thought she was grading papers, but what they realized later was that she was writing. She worked at the school for a year and a half, however, because there was a delay in obtaining her teaching certificate, she was fired. It was just a few months later that she suffered a stroke and ended up at a nursing care facility, where she would die from a second stroke on January 29, 1960. Hurston's friends and her greater community raised money to pay for her funeral and burial. Her funeral was held at Peek's Funeral Chapel on Sunday, February 7, 1960. Hurston lay in "A frilly pink dressing gown" surrounded by flower arrangements that had been sent from around the country. Below are excerpts from the obituary printed on the funeral programs:

Miss Hurston was one of America's foremost women authors. Her short stories and articles have appeared in Opportunity, Story, Ebony and Topaz, and the Saturday Evening Post. Her works, largely from folk sources, include Mules and Men, Jonah's Gourd Vine, and Their Eyes Were Watching God.

She has worked in many capacities. At one time she was amanuensis for Fannie Hurst, noted novelist. She served as drama coach at North Carolina College for Negroes; as a principal speaker at the annual Boston Book Fair; as a librarian in the Library of Congress and at Patrick Air Force Base, Cocoa, Florida; and as a substitute teacher at Lincoln Park Academy, Fort Pierce, Florida.

Her personal life was as the fragrance of a beautiful rose, and her influence will ever live in whatever places she has resided. She was quiet in her manner and pleasant toward everyone. To use her own words: 'I love courage in every form. I worship strength. I dislike insincerity, and most particularly when it vaunts itself to cover up cowardice. Pessimists grouches, and sycophants I do despise.

After the funeral, her casket was taken to the Garden of Heavenly Rest, where Reverend Jennings gave a moving eulogy, "They say she couldn't become a writer recognized by the world. But she did it. The Miami paper said she died poor. But she died rich. She did something." (160).

When J.J. and I pulled up to Genesee Memorial Gardens Cemetery (formerly called Garden of Heavenly Rest), it no longer looked like the abandoned lot Walker found the day she visited trying to find Hurston's unmarked grave. Walker waded through weeds up to her waist to try and find the place where Hurston had been buried calling out Hurston's name asking for her to tell her where she'd been buried. All she knew at the time is that Hurston was buried near the center of the plot. When Walker’s foot slipped into a hole, she realized she’d found what appeared to be a sunken grave at what appeared to be the center of the lot.

Thanks to Walker and many others, J.J. and I walked up to a well-marked grave with a headstone (placed by Walker) that reads: Zora Neale Hurston A Genius of the South" (a quote from Jean Toomer's Cane). Many had left offerings and we left our own — a mug filled with flowers we'd picked at J.J.'s house.

My trip to Hurston's grave offered me a reminder of the role we all play in remembering the lives of those who came before us. Especially in times like these, it's crucial that we remember the voices that have come before us.

Upcoming Events

Come join me at one of my upcoming events!

March

Thursday, March 27th at 1:00: Iris Jamahl Dunkle will be signing her new biography, "Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb" in Booth 926 at the Catamaran table at AWP

March 30, 4:00-5:30 PM, Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the Occidental Center for the Arts, Occidental, CA

April

April 12 - 3:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at Full Circle Bookstore, Oklahoma City.

May

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA

what an amazing book tour -- and pilgrimage

To be forgotten in the town where you came from is harsh. For many years my hometown overlooked Edna Ferber and her literary legacy. Now there is an elementary school named after her and a growing appreciation of her place in the American canon.