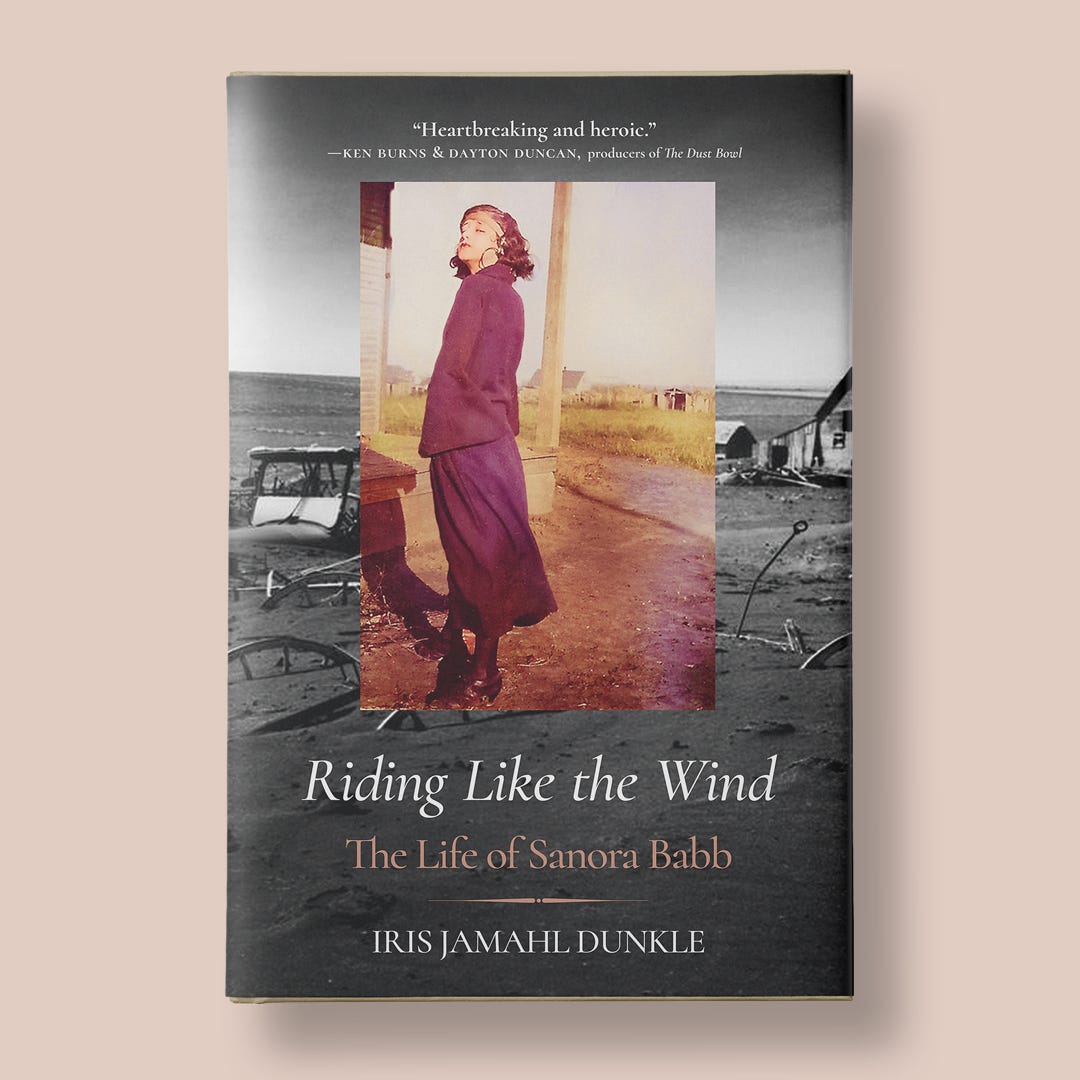

My biography about Sanora Babb’s life, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb (University of California Press) will be published in six weeks. It’s so exciting to reach this point after years of hard work researching her life. I started writing about Babb when I saw her featured in the Dust Bowl documentary by Ken Burns, which features her story. Over the next six weeks, I’ll post a few posts about Babb, her books, and some of the incredible people she interacted with throughout her life.

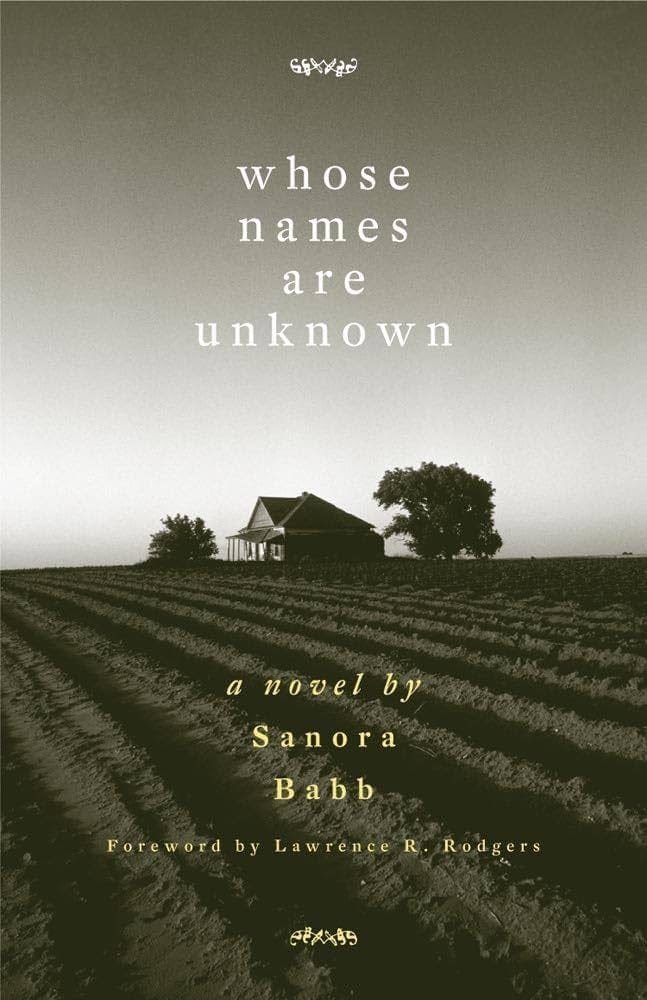

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the publication of Sanora Babb's classic novel, Whose Names Are Unknown (2004) —A book that didn't get published when it was originally written and under contract with Random House in 1939 because John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath was published just three weeks before. Their books shared a lot of similarities, likely because Steinbeck borrowed her notes during a visit to the camps where Babb was working.

The novel Whose Names Are Unknown is titled after an eviction notice Babb saw on a decrepit shack on a corporate farm. She thought the title conveyed how to the big corporate farmers saw the migrants who’d lost everything and came to California seeking work and who then toiled for pennies a day. The migrants were not thought of as being human. Babb had observed this base behavior during the eight months she spent working for Tom Collins, helping run the FSA camps.

The book, set during the beginning of the Dust Bowl, is divided into two parts. The first is set in the panhandle of Oklahoma. The second is set in California. Whose Names Are Unknown begins BEFORE the disaster of the Dust Bowl. In the opening chapters, we meet Milt Dunne, his wife Julia, and his two daughters, living in a dugout on farmland in the panhandle with his father, Konkie (modeled after Babb’s grandfather). We watch as they decide to switch crops — choosing to farm wheat instead of the less water-demanding broomcorn.

When old man Dunne first filed his claim on a half-section of farmland he found it to be a piece of flat grassland in the midst of thousands of acres of free range. He broke sod and planted row crops, and the lean range cattle overran his fences and devoured his crop. In the winter when they drifted with the storms, sometimes the cattle came through his fences and hovered about in the slight windbreak of his dugout and barn.

Then, as more men filed claims and crops began to appear in the range country, a fence law was voted, and the cattlemen had to keep their herds on their own land. There was a great and angry to-do among the ranchers. Many of them refused to fence for a long time, and on the sparsely settled plains no one enforced the law favoring the farmers.

The old man recalled vividly the first year he raised broomcorn, how he made himself two sturdy hand-wired brooms, one for the dugout and one for sweeping the bare yard around the door. Now he was going to venture winter wheat because his son Milt said there was more money in it. (4)

We get to know the characters—their love of the land, devotion to hard work, and family dynamics. We see their joys alongside the tragedies they suffer. Then, we watch as the Dust Bowl slowly unfolds. For example, in Chapter Seventeen, we read diary entries by Milt’s wife, Julia, as she records the horrors that unfold as the dust storms become more frequent.

Dad boarded up the windows this morning as the dust was still blowing, looking like it would never stop Julia brushed the dust from the rough school tablet paper and looked back at what she had written. She had decided to keep a record of the strange phenomenon of dust. The old man kept a record for years of the great storms, droughts, deep rains. He named the day and the year of natural disturbances the way another man names the events of his life. She read her description of the first storm and felt frightened again, and pleased with herself. She closed the tablet and placed it on a shelf and went about her work.

April 4. A fierce dirty day. Just able to get here and there for things we have to do. It is awful to live in a dark house with the windows boarded up and no air coming in anywhere. Everything is covered and filled with dust.

April 5. Today is a terror.

April 6. Let up a little. We can see the fence but can't see any of the neighbors' houses yet. No trip to town today. Funny how you learn to get along even in this dust.

April 7. A beautiful morning. Everyone spoiling the happiness of a clear day by digging dust. Sunday afternoon we walked for miles to see other places. It was a sight. It looks like the desert you read about in books, desolation itself. The day began and ended as a real sunshiny western day.

April 8. Morning bright and skies clear. Ten o'clock. Dirt began to show up around the edges. By noon the sky and air full. We try to do our work as usual, thinking rain may fall and end our troubles for a while. We don't speak much of the wheat anymore. Going to bed. Dirt still blowing. (90)

By using this approach, we know who the Dunne’s were before the worst day of their lives when they had to make the impossible decision to leave their farm and everything they’d known behind to try and find work out west.

Babb’s approach to humanizing her characters spoke to me deeply for several reasons. First, because I live in a place that was devastated by disaster. In 2017, the Nuns, Tubbs, and Pocket Fires (together comprising the Sonoma Complex Fire) burned over 110,700 acres in Sonoma and Napa counties. The Tubbs Fire alone destroyed more than 5,600 structures, including over 2,800 homes in Santa Rosa, California. So many people’s lives were upended overnight. If you’d met them on that day or the terrible weeks after, as the fires still burned, you wouldn’t have seen them for who they were entirely. I loved how Whose Names Are Unknown made us see the humanity in those suffering through the worst disaster of their lives because we got to know them before disaster struck.

Second, Whose Names Are Unknown spoke to me because my grandmother came over in the Dust Bowl and never liked how John Steinbeck depicted people like her in his book. I never understood this until I read Whose Names Are Unknown and saw what was missing from Steinbeck’s book.

Babb was able to humanize her characters because she lived amongst them. She interviewed 781 families while she was working at the camps and writing her book. Plus, she knew what it was like to live in a dugout and subsist on the crops you raised. She spent her early years living in a dugout in Eastern Colorado, where her family farmed broomcorn and faced starvation.

I hope this post has made you order Babb’s book! If you are interested in a reading guide for the book, sign up to be a paying subscriber! I’ll be posting chapter-based reading questions for my paid subscribers next week!