Finding Lost Voices: The Case for Amy Lowell and the Scholarship Focused on Bring her Legacy Back (1874-1925)

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

I will be going on a research trip to England, May 21–29, and am looking for donations to help cover the cost. If you appreciate the work I’m doing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to this Substack. Every dollar I receive goes to researching the lives of forgotten or misremembered women.

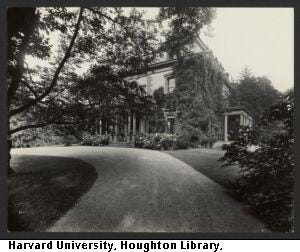

As a biographer, one of the things you’re always looking for is the crack between the story the public thinks it knows about a person, and the clues that reveal another story that’s been hidden underneath. When I finished writing my dissertation on Amy Lowell’s poetry and her influence on modern American poetry, I visited Boston. I took a cab to the address of her home in Brookline. What I found shocked me. The elegant mansion, Sevenels, had been subdivided into several parcels. The lush garden Lowell wrote about in her poems had been ripped out, and perhaps most shocking, the top floor Lowell had added to the house (which she dubbed the “Sky Parlor”) had been completely removed.

The Sky Parlor was Lowell’s bedroom, where she wrote many of her works while looking out its large windows at her garden below. The house, and how it had been mistreated, seemed like a metaphor of how Lowell’s life and legacy had been neglected since her untimely death at age 51. (If you missed last week’s post giving a brief overview of the life and work of poet Amy Lowell, you can find it here.)

During her lifetime and shortly after, many of Lowell‘s books became critically acclaimed best-sellers; What’s O’Clock was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1926. Her popularity was something Lowell took seriously. As she wrote to Richard Aldington, “poetry ―is and must be universal, above the customs and the cliques of the initiated.” Her belief that poetry should be ―both innovative and accessible‖ would help democratize poetry as it was being written in the United States during and after her lifetime. This concern with accessibility stands at odds with the disregard for an audience that we associate with modernism. One of Lowell‘s guiding principles as a poet was to insist that her work be not only self-expressive but communicative. She believed poetry was a spoken art. Her determination to connect with her audience and her commitment to developing a popular poetics made Lowell one of the leading voices in American letters by the time she died in 1925.

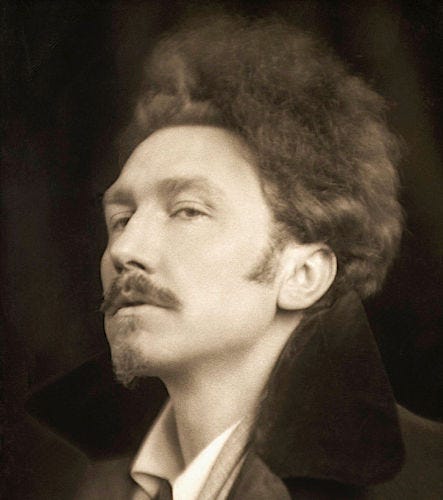

When Lowell died, her colleagues and friends mourned their loss but found solace in the idea that her poetry would inevitably leave a lasting mark on twentieth-century literary history. They could not have fathomed how completely Lowell would be marginalized after her death. Lowell‘s popularity soon began to fade, and ad hominem attacks undermined her critical reputation. Today, aside from a few anthologized poems (her poem “Patterns,” for example), most of Lowell’s poems are out of print, and she is remembered not for her innovative poetry but for her quarrels with Ezra Pound over the Imagist movement, as well as her larger-than-life character and physical presence. What has happened since her death to leave her work in such obscurity?

This week, I turned to two Amy Lowell scholars, Melissa Bradshaw and Carl Rollyson, to answer that question and learn about the incredible work being done to recover her important career. For paid subscribers, I’ll also send out a second post featuring some of my favorite poems by Amy Lowell.

To begin with, I interviewed biographer Carl Rollyson. Rollyson is an esteemed biographer who has published more than forty books. What follows is an excerpt from our conversation about his work on Lowell in Amy Lowell Anew: A Biography and Amy Lowell Among Her Contemporaries.

Dunkle: Why is so much of Lowell’s story missing? And how were you able to overcome that as a biographer?

Rollyson: Lowell destroyed any evidence of her love life. Her last lover, Ada Russell, cooperated and burned their letters. It was a very private relationship. You can understand why she did it, but as a biographer, it grieves me that we don't have their correspondence. Like many biographers, I thought, well, [all the archival material] is there at Harvard, I have to go to Harvard and read through it all, which I did. But while I was working on researching my biography an archivist at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston found previously uncatalogued Amy Lowell material and reached out to me. That’s when I realized that there may be stuff in other places. Just because biographers say, this is the archive that doesn't mean that's the whole archive. And so thanks to this contact, I found information about her earlier life about a lover who had died on the Lusitania, in 1917. So that's a story I tell for the first time in my biography.

[Rollyson writes about Lowell’s relationship with Elizabeth “Bessie” Seccombe in Amy Lowell: Anew 20-24]

Rollyson: I also wanted to rehabilitate Lowell not just as a poet but also correct a skewed view of her as a human being—isolating her from people in her erotic life and her love life, but also in her connections to modern poetry and how she behaved among her fellow poets. She had a 10-year love affair with Ada Russell, but how do you deal with someone who is really important, and yet the letters are gone? I did it by looking at how Lowell traveled a lot. And so I could determine, because of the letters she wrote to various people who would often mention, “Oh, say hello to Ada.” Then I knew Ada was with her and was in the room, and that's important.

When Lowell went to London before World War I, for example, the first time she met Ezra Pound—who was already a force in modern American poetry—she essentially had to face down this guy because you were either with him or against him. To Pound, Lowell was an interloper. Who was this society lady who thinks she knows how to write poetry? But when Lowell had Ada Russell with her—and Ada Russell was a very different sort of person. She was an actress…an incredible diplomat. She was present at key Imagist meetings that have been widely described in Pound biographies and early Lowell biographies—but her presence is never mentioned. This makes all the difference. It bolstered Lowell's confidence. It gave her a sense of herself.

Dunkle: Why do you think Amy Lowell is an important figure in the American canon?

Rollyson: She was a true groundbreaker. Her groundbreaking approach put her at odds with figures like T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. Lowell believed that poetry wasn't just for the esoteric, for a closed circle. She wanted to broaden the appeal of poetry, but that's often misunderstood.

Dunkle: With women who have been misremembered, you often have to like look elsewhere in order to find their archives. You mentioned the the Massachusetts Historical Society as a place outside of The Amy Lowell Collection at Harvard where her main archive is stored. Where else did you find extra materials?

Rollyson: Mostly in the archives of other people. There were some archival materials in England because she had done a biography of John Keats, and so I found correspondence in other people's archives in England. She was often identified in biographies of other people, so I wrote Amy Lowell Among Her Contemporaries to show her actual interaction with Robert Frost, Carl Sandberg, Ezra Pound, and D.H. Lawrence.

When she was writing her biography of John Keats, she behaved like any other biographer looking for letters. She was talking to Keats collectors—mostly male—and you can see in her correspondence when she writes to other people. She says, “I'm trying to get this stuff out of this guy. He's a Keats collector, and I've got to be really nice or I'm not gonna get this stuff from him.” That tells you so much about her. Yes, she had this brash, sometimes even arrogant persona. It's not that it wasn't true, but that's all people seem to know about her. She also had a whole other side—patient, strategic, diplomatic—especially visible in her biographical research. That was part of my effort to recapture the whole human being. There's a chapter on her Keats biography in my book (pp. 179–188), and it was to show that aspect of her. She was quite aware of what she looked like and what people said when she walked into a room—which is why Ada Russell was so important. Ada gave her a source of strength and support. She helped humanize Lowell in a way the public rarely saw.

Dunkle: Thanks so much for speaking with me about your biographies about Amy Lowell!

I first encountered Melissa Bradshaw’s work through a collection of essays she co-edited with Adrienne Munich, Amy Lowell, American Modern, which I relied on heavily while writing my dissertation. Since then, Bradshaw has published an extraordinary monograph, Amy Lowell, Diva Poet, which applies theories of the diva and female celebrity to explain Lowell’s remarkable literary influence in the early twentieth century—and her equally remarkable disappearance from American literary history after her death.

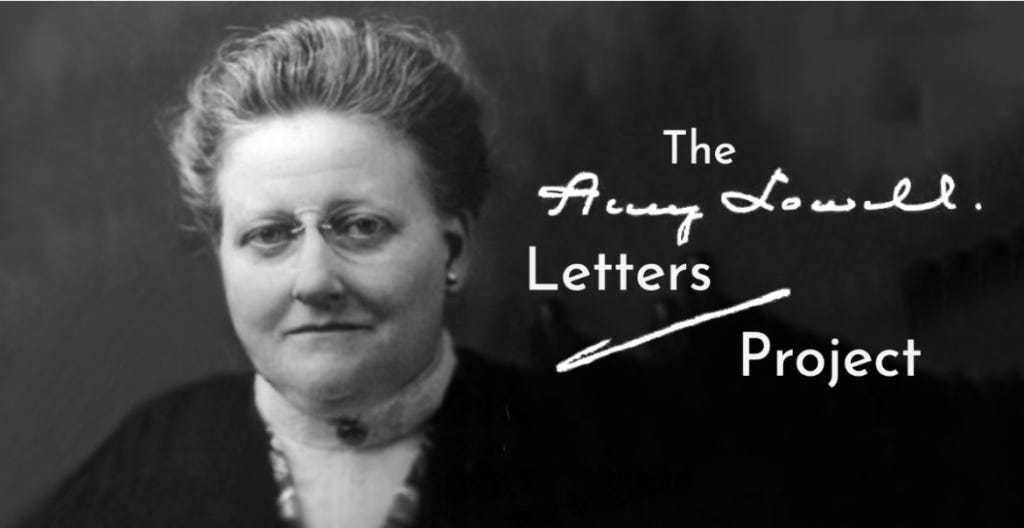

For the last five years, Bradshaw has been leading The Amy Lowell Letters Project (ALLP), an open-access, digital scholarly edition of the letters of American poet, editor, and critic Amy Lowell (1874–1925). Her work has collected thousands of Lowell’s letters at Harvard. A project as she explains, that isn’t just about bringing back the life of an essential American poet,

“It’s irrelevant to me whether people believe that Lowell is worth remembering as a poet,” Bradshaw told me. “I think she is. I think her poetry and its continued popularity speak for themselves. But what Lowell’s letters show us is that when you take someone like her out of the equation, you’re missing a node in a tight network. She wasn’t just connected to other poets—she was in constant contact with magazine editors, publishers, journalists, and critics.”

Bradshaw first conceived of digitizing Lowell’s letters while working in the archive at Harvard. “Beginning in 1913, Lowell had secretaries, so she had all her correspondence typed in duplicate and saved the carbon copies. You can go through them all. And then there are the responses—Lowell wrote to over 1,400 recipients. I thought, what if we could get them to talk to each other through digitization?”

Bradshaw knew that by digitizing Lowell’s letters, we would not only recover her life, but we’d also recover the vast publishing landscape she was a vital part of. Bradshaw and her team have made the letters completely searchable using XML.

By using XML encoding, Bradshaw and her team have made thousands of letters not just searchable but richly interconnected. Users can search not only who wrote or received a letter, but also who is mentioned within one. “I want this to be a place where scholars of modernist poetry, publishing history, or American book culture can come and plug in a name—and find them, even if they’re just a passing reference,” Bradshaw explained.

The project also reveals how moments in Lowell’s life were seen and described from multiple perspectives. For instance, her feud with Ezra Pound over Imagism—often the defining footnote in her legacy—can now be traced through Lowell’s letters to Pound himself, to Harriet Monroe, to William Carlos Williams. “We want to track not just where she talks about the feud, but for how long—and to whom,” Bradshaw said.

One of the most powerful aspects of Bradshaw’s approach is how she has incorporated the project into her teaching at Loyola University. “For five years, I’ve been teaching The Amy Lowell Letters Project as part of my courses. Right now, I’m teaching a graduate seminar in textual studies, where students are helping to create editions from unprocessed archival material.”

This semester, her students are editing 27 letters Lowell wrote to her father and sister-in-law while traveling in Egypt in 1897-1898. Previous biographers often described this trip as a kind of “fat camp” Lowell’s father forced her to attend after a failed engagement, supposedly leading to ill health and a nervous breakdown due to the spartan diet. But through the letters, a different version of events emerges: one of an athletic, confident, curious woman exploring the world on her own terms.

“It’s a completely different story,” Bradshaw said. “And that’s what happens when you go back to the original sources.”

It’s been fifteen years since I visited Lowell’s house in Brookline, Massachusetts, and it heartens me to learn of the recovery work that’s been done since that time. For paid subscribers, look for an upcoming post that includes some of my favorite Amy Lowell poems and some Carl Rollyson and Melissa Bradshaw recommended.

For More Information:

Amy Lowell Anew: A Biography by Carl Rollyson

Amy Lowell Among Her Contemporaries by Carl Rollyson

Amy Lowell, Diva Poet by Melissa Bradshaw

The Amy Lowell Letters Project (ALLP)

Upcoming Readings and Events

May

May 16 - 6:00 PM 36th Annual Oklahoma Book Awards - Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb nominated for nonfiction, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, 1700 NE 63rd St., Oklahoma City, OK

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA

May 20 - 6:00 - 8:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Dana Gioia and Elise Paschen Reading at Dominican Edgehill Mansion 75 Magnolia Avenue San Rafael, CA 94901