Finding Lost Voices: The Acid Queen - Rosemary Woodruff Leary(1935-2002) and my interview with Susannah Cahalan

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

I grew up with hippy parents, so I’ve never been one to romanticize the hippy generation. When you are a child growing up in a hippy family, it isn’t glamorous or noble. It’s hard. In my case, we lived in a trailer next to a condemned house. We grew our own food and got creative sometimes about what we ate, even going so far as to eat fresh roadkill. We didn’t have a TV. At one point, all my mom had to cook off of was a wood-burning stove. It was a life that my dad had chosen (my mom would have happily had an electric stove), and I saw firsthand what imbalance there was between the sexes in this supposedly evolved counterculture.

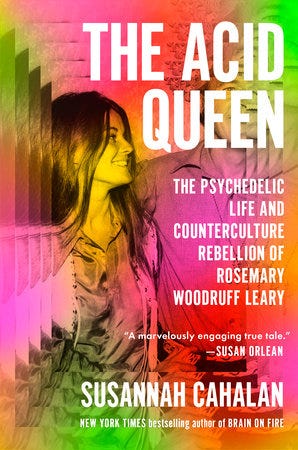

Because of my real-life experience, I am often skeptical when people romanticize figures from the 1960s. Especially, counterculture heroes like Timothy Leary, who was known for his strong advocacy of psychedelic drugs like LSD. So, when I picked up Susannah Cahalan’s recent biography, The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary, I was cautious. Would this just be another hero-worshipping text that glamorized the psychedelic movement? When I began reading, I immediately realized the answer is no. Cahalan’s book gave me a more in-depth perspective about a complicated time in American history, one where the stories of women had been all but erased. While getting to know this era, I also got to know an incredible woman I had never heard about: Rosemary Woodruff Leary (1935 - 2002).

So, who was Rosemary Woodruff Leary, and why have you never heard about her before? Well, let’s start with the obvious. She was much, much more than just someone who was married to Timothy Leary. As Cahalan points out early in her book, Rosemary is the face you’ve seen but never recognized before. Her face and her words are everywhere in the counterculture movement. In the video of John Lennon recording “Give Peace a Chance,” Rosemary is there singing along, laying in bed next to Yoko Ono. She helped her husband, the ex-Harvard professor who turned into an acid guru, craft the slogan, “Turn on, tune in and drop out.”

Rosemary met Leary at the Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, NY, where he was running psychedelic retreats. And the two were soon married. For the next seven years, Rosemary stood by Leary’s side as his fame grew: sewing his clothes, making his dinners, and taking care of his two children from a previous marriage. She was also instrumental in helping him write speeches and crafting his image. And, in what won’t be much of a surprise for those who read this Substack regularly, she helped him write many of his books and never received credit. In 1970, Rosemary even assisted Leary escape prison and fled to Algeria, beginning a 25-year-long fugitive journey across four continents. But while Leary’s story survives after this exile, Rosemary’s does not. Lucky for us, Cahalan’s book changes that.

Recently, I sat down with Cahalan to discuss what drew her to writing the book, how she came upon Rosemary’s story, the almost psychedelic experience of archival work, and the importance of including (and feminizing) the index in a biography about a woman who has been forgotten.

Iris Dunkle:

What drew you to tell Rosemary’s story?

Susannah Cahalan:

My first book, Brain on Fire, was about my own experience with altered consciousness and how fragile our perception really is. That curiosity carried into my second book, The Great Pretender, where I looked at how altered states, like with ketamine or hallucinations, affect memory and behavior. I also wrote about Humphry Osmond, the psychiatrist who actually coined the word “psychedelic.” He even had architects take LSD while designing hospitals. That was wild! Back in the day, LSD was seen as a way to mimic psychosis, but later folks realized it had real healing potential. Timothy Leary, though, took it in a very different direction.

I kept hearing about psychedelics from psychiatrists and friends doing ayahuasca trips, so I got interested. While I was researching at the New York Public Library, I stumbled on Timothy Leary’s huge archive, and then found Rosemary Woodruff Leary’s smaller but fascinating collection. I hadn’t heard of her before.

Right before COVID hit, I bought this black poppy dress at a Brooklyn boutique, and later found out it was inspired by Rosemary. It felt like a sign, her influence is quiet but powerful. The designer, Karin Rågfors, said she felt the same pull. I didn’t get the dress but did snag a Rosemary-inspired kaftan with peace signs and yin-yangs, a fun piece that really connects to her spirit.

Iris Dunkle:

Isn’t it fascinating when real life intersects with your archival work? It feels like the universe is nodding at you.

Susannah Cahalan:

Totally. I know you get this—anyone deep into archival research does. It’s almost a psychotic state, where you start seeing connections everywhere, whether they’re real or not.

Iris Dunkle:

It’s a great feeling—deep focus.

Susannah Cahalan:

Exactly. Everything starts to feel connected. It’s not psychosis—it’s psychedelic. That sense of interconnectedness is what we’re chasing through religion, through psychedelics. And you can feel that same transcendence in the archives.

Iris Dunkle:

Yes, though there are plenty of boring parts in between.

Susannah Cahalan:

One hundred percent! But those moments when it all clicks? That’s transcendence. Rosemary’s story had a lot of synchronicity. It was a fun, vibrant topic—very different from my second book, which dealt with severe mental illness and hospitalization. That book had its moments, but this was just… more joyful to write.

Iris Dunkle:

Let’s go back to Rosemary’s early life. In the book, it seemed like her story was told through the lens of the men she was involved with—until she met Timothy Leary. Did you follow her lead in telling her story that way?

Susannah Cahalan:

Yes, basically. That’s what I had to work with—and it was also a real pattern in her life. She was a high school dropout, moved to the city with no money. Her options were extremely limited. In many ways, she expressed her greatness through the men she chose. Understanding her life means understanding the men around her.

In her writing, her diaries, her unpublished memoir, she makes it clear she saw herself as a great woman who should have been part of the historical record. But she believed her path to that greatness was through supporting great men.

Iris Dunkle:

She really didn’t have any other path.

Susannah Cahalan:

Exactly. She was stopped on the street by Eileen Ford and became a model, a stewardess. That alone would be enough for some people, but for her, it was a means to an end. And that end was supporting greatness. When she met Leary, she thought she had found her purpose. But the reality of being "the woman behind the man" didn’t fulfill her. Only later, on her own, did she really come into her own.

Iris Dunkle:

I appreciated how you highlighted the sexual violence many women faced during that era—including Leary’s daughter. It’s heartbreaking. Why do you think the Peace and Love era often avoids confronting this?

Susannah Cahalan:

It’s partly because Rosemary represents a shift, from the “old guard” of overt physical abuse to more subtle psychological and ideological violence. On communes, sexual liberation was touted, but boundaries were often ignored, and terms like “frigid” were weaponized against women. Many young women were exploited or damaged, but their stories went untold.

Iris Dunkle:

Right, those stories are missing from the historical record.

Susannah Cahalan:

Exactly. Most academia overlooks hippie women as a movement. The women I spoke with were strong and still live by those values, but sexual politics were harsh. Women had little ability to set boundaries and were often pressured into sex just to keep the peace.

Iris Dunkle:

Men still held the power.

Susannah Cahalan:

Yes. Timothy Leary came from an earlier generation. Women did the caregiving, chores, and tended bad trips. That hidden labor, mainly by women, underlies today’s psychedelic renaissance. Rosemary embodied that.

Iris Dunkle:

Her memoir was never published, right?

Susannah Cahalan:

Right. She tried, but publishers weren’t interested. Her family, especially her brother Gary, supported telling her story honestly. That was rare and vital.

Iris Dunkle:

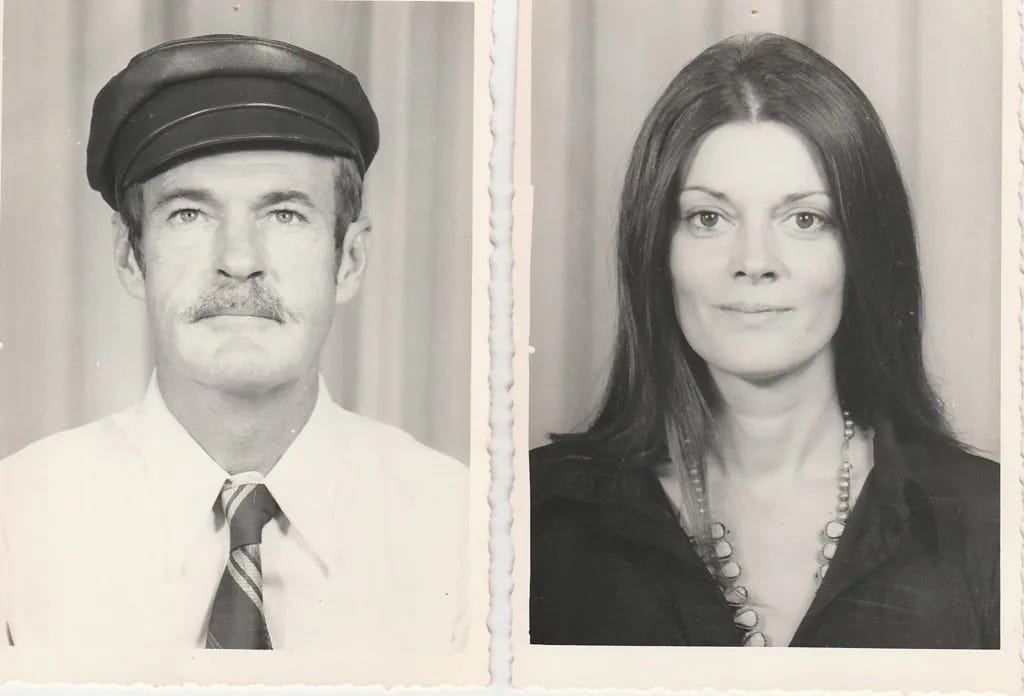

Gary saved her archives, didn’t he?

Susannah Cahalan:

Yes, for decades in his garage. He even said he understood her better after reading my book. It’s a privilege to have that trust.

Iris Dunkle:

Family can block stories, especially of women who were forgotten.

Susannah Cahalan:

Absolutely. Gary told me, “Tell the truth.” Some details aren’t flattering, but that honesty is important.

Iris Dunkle:

You also suggest Rosemary helped write some of Timothy’s books?

Susannah Cahalan:

She did, especially High Priest and Politics of Ecstasy. She co-wrote Diary of a Drug Fiend, but wasn’t credited. Timothy called her only “Her.” She fought legally but couldn’t risk coming back to the U.S.

Iris Dunkle:

How did you “feminize” the index of your book?

Susannah Cahalan:

Initially, I didn’t want one—it was expensive and the book was long. But you convinced me to prioritize women’s names. Many had never appeared in indexes before. It makes these women part of history now.

Iris Dunkle:

That’s essential for future research.

Susannah Cahalan:

Yes. Some dismiss “feminizing the index,” but it’s serious. I’m proud to have done it, and you’ve changed how I see indexes forever.

For More Information

Read The Acid Queen: The Psychedelic Life and Counterculture Rebellion of Rosemary Woodruff Leary by Susannah Cahalan

Psychedelic Refugee: The League for Spiritual Discovery, the 1960s Cultural Revolution, and 23 Years on the Run by Rosemary Woodruff Leary

Also by Susannah Cahalan: Brain on Fire and The Great Pretender

Watch Bed Peace Starring John Lennon and Yoko Ono (1969), where Rosemary Woodruff Leary appears (and sings).

![High Priest LEARY, Timothy [Fine] [Hardcover] High Priest LEARY, Timothy [Fine] [Hardcover]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!o6NZ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4bc3500c-a540-4a1c-b775-74ea11cee131_152x177.webp)

This is so refreshing and enlightening ~ and without drugs! Thanks for the good interview and discussion of this important life story. Brava!

Fascinating to learn more about Rosemary Leary. Adding this new biography to my TBR list. Thanks!