Finding Lost Voices: Mary Hallock Foote (1847–1938) and the Theft of Wallace Stegner

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

Growing up, I loved three novels: Jack London’s Valley of the Moon, John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, and Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose. By the time I was in my teens I’d read these books so many times I’d memorized long passages from them. Why did I love these books? Mainly, for two reasons, each was set in the California landscape that I loved, and was vivid with the geography of the West. And also each of these works had strong, female characters I could relate to. There seemed to be a dearth of female protagonists and characters in Western Writing. So, I clung to these novels as if they were lifeboats.

So many years later, what I’ve come to realize is that each of these authors had another thing in common. Each appropriated content from female writers without giving credit to the women they borrowed work from. I’ve written extensively about London’s collaboration with his wife, Charmian Kittredge London’s on The Valley of the Moon in my biography Charmian Kittredge London: Trailblazer, Author, Adventurer. And my most recent book, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb reveals Steinbeck’s appropriation of Sanora Babb’s detailed content for his book, The Grapes of Wrath. But, I’ve never written about the third controversy: Stegner’s theft of the writing and life of Mary Hallock Foote (1847 - 1938) in his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Angle of Repose.

So, this week, I’m diving in. Mary Hallock Foote was so much more than a woman maligned by Stegner’s actions. This post aims to bring back the life and work of one of the most acclaimed American authors and illustrators of the late 1800s and early 1900s you’ve never heard of. A woman who wrote about the American West from the perspective of a woman.

Mary (Molly) Hallock (Foote) was born on an old farm in the Hudson Valley a half a mile from Milton, N.Y in 1847. She had three siblings and lived with her parents and grandparents on the farm that had been established by their Quaker descendants in 1762. From their two-story home they could see the Hudson River that teemed with boat traffic during most of the year including steamboats carrying passengers and supplies between New York City and Albany, NY. In the winter, the river iced over and held its breath. Life in the Hallock household was enriched by literature. Her father would often read aloud to the family at night the poetry of Tennyson, Scott, Burns and Cowper. And whenever luminaries such as Fredrick Douglas or Susan B. Anthony came through Milton to give a talk they often ended up at the Hallock fireside for further discussion afterward.

As a child, Mary liked to draw. In her memoir she remembers she was called “the artist of the family.” When she attended and boarded at the nearby Poughkeepsie Female Seminary in her teens she was given art lessons by Margaret Gordan, the head of the school’s Department of Painting and Drawing and through this work was able to develop a portfolio. After she graduated, Her sister in-law Sarah Walter Hallack was so impressed with Mary’s art that she took it upon herself to convince Mary’s parents that they should let her attend The Cooper Institute (Now, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art) at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper, who founded the school believed education should be free and open to all who qualify, regardless of race, gender, or social status. And so just a few weeks before her seventeenth birthday, Mary moved to Brooklyn Heights to live with Sarah’s family.

While at The School of Design for Women at Cooper Institute, Mary lived her life immersed in art. As she later remembered, “I remember only being…gloriously happy all those months.” During the winter of 1867 while still studying at the Cooper Institute she met her fellow classmate and soon to be lifelong best friend, Helena de Kay (on whom she would base her 1917 novel, Edith Bonham). Their friendship was deeply important to both of them. Mary would call it “the first great passion of my life.” They each believed they were able to bring out the best in one another. Helena was outgoing while Mary was more reserved. On Fridays during anatomy lectures they’d write notes to each other in the margins of their notebooks. Afternoons they’d spend working on their art together in the open studios or sitting in alcoves of the school “comparing our past lives and dreams for the future.” Helena gave Mary a book of Emerson’s poems and introduced her to the writing of Mathew Arnold and John Stuart Mill. As Foote would later reflect in a letter to Helena, “your mind has led mine for a good many years.” The two would correspond for the rest of their lives.

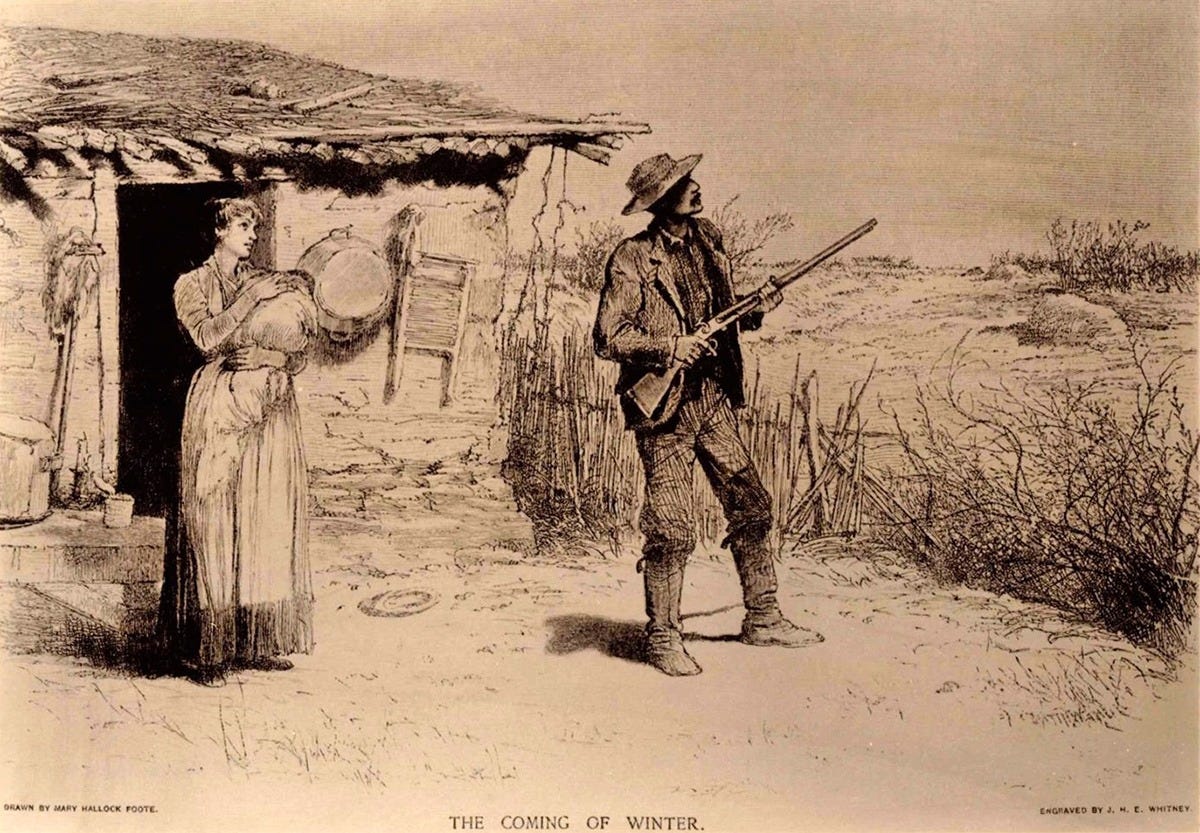

Early in her time at Cooper Institute Mary decided to focus on black and white commercial illustration and she had two main mentors who helped her develop her craft: the sculptor, painter and physician, Dr. William Rimmer and the poet, printer and wood engraver, William James Linton. She would become an expert at wood block engraving. By 1871 she had become a highly sought-after book illustrator for top writers, including Hawthorne, Longfellow, and Tennyson. One of Foote’s first commissions was for an engraving that was featured in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Hanging of the Crane, in 1874. When the New York Times reviewed the book the author noted that her “drawings reveal the hand of a thorough artist and…are as full of poetry and feeling as Mr. Longfellow’s lines.” Hallock would go on to be recognized as “the dean of illustrators” and be elected to the National Academy of Women Painters and Sculptors.

On New Year’s Day in 1872, Mary and her family visited the Walter’s home in Brooklyn Heights. While she was in the study, escaping the crowd of relatives to work on an illustration, a young man walked in and, seeing her drawing, asked if he could stay while she worked. Mary blushed but agreed (but was nervous she wouldn’t be able to work while Arthur was in the room but was relieved to realize that she could). They began talking and she learned that Arthur had studied engineering at Yale. The day he met Mary, he’d already decided to continue his engineering education in a more practical way — in the field and after a few months of courting, Arthur set out to the West to find work, promising Mary he would return for her once he’d found his vocation.

At the same time that Mary met Arthur, Helena had also fallen in love with a publisher named Richard Watson Gilder. But, both Mary and Helena were cautious of getting married as they were worried that once they became wives and then mothers, they would no longer be able to pursue their lives as artists. But both of them took the risk. In the Victorian Era, this was a real fear, and the balance between their art and lives as wives and then later mothers would be a long struggle for both women throughout their lives.

When Arthur returned from the West, the two were married in February 1876. After a brief honeymoon, Arthur had to return to San Francisco. A few weeks later, Mary joined him. She said goodbye to all she loved and boarded the Overland Limited to San Francisco. Riding on the train across the country she worked on her commissioned engravings for The Scarlet Letter as the landscape flew by the train’s window. Mary was always looking, and she couldn’t take her eyes off of this new world of the West where she had landed. When she finally arrived in San Francisco, after a brief rest, she and her husband took a stage through the great oak forested valley of San Leandro to the quicksilver mine called New Almaden, where Arthur was working, and they would be living for the next year. This mine would be the first of many rugged places that she would live in over the years in California, Colorado, South Dakota, and Idaho.

Soon after moving, Mary became lonely. She missed her family, and she especially missed Helena. She felt free yet isolated out West. So she began writing long letters to Helena. When Helena’s now husband read these letters, he had an idea. Why don’t you write about your experiences in New Almaden for Scribner’s? He asked in a return letter. Mary hesitantly agreed. Prior to writing this article, she had only ever published a children’s story, and she wasn’t sure she could write the way she’d need to write for a national audience. But Helena and her husband assured her and offered to help. Mary’s story, “A California Mining Camp,” along with fourteen of her illustrations, appeared in the February 1878 issue of Scribner’s. She was paid $300 (almost $10,000 today) for her work. Helena had assisted her friend in selecting passages from her letters and helped with editing the work. So much so that Mary felt the publication was as much Helena’s as it was hers. In the article, Mary writes about her year living in the mining camp from the perspective of an embedded reporter, and this inside look into this life was a huge success. What was extraordinary was how she captured the miners’ lives with an eye toward everyone in the community: the women, the children, and the diversity of people living together in the mining town.

Shortly after finishing the article in 1877, Mary gave birth to her son, Arthur Burling Foote (in the following years, she would also have two daughters, Betty (b. 1882) and Agnes (b. 1886)), and their family relocated to Santa Cruz while Arthur went back and forth to San Francisco developing his next business venture: cement. In Santa Cruz, Mary had to juggle the life of an artist with her new life as a mother while her husband was often away. Luckily, she’d already established herself as one of the preeminent illustrators in America at the time, so the demand for her work and the payment she received for it enabled her to afford the help she needed to allow her to continue to work. In Santa Cruz, Mary worked on a series of illustrations for Louisa M. Alcott’s “Under the Lilacs” and continued to write short stories set in Santa Cruz.

The next move their family made was to the booming mining town of Leadville, CA, which proved to be a gold mine of stories for Mary to write about. Led-Horse Claim: A Romance of a Mining Camp (1883) would be her first novel, written from the point of view of a woman living in the mining town. In her memoir Mary remembers how originally the novel had ended with the lovers parting ways but Scribner’s wouldn’t hear of it and insisted she write a happy ending instead.

As an artist, Mary had an eye for natural descriptions and its these photographic-like details that drew readers into the Western settings of her stories. As she recalls, “ I cannot write a story without seeing the places.”

From Leadville, the family moved to Mexico, then on to Boise Idaho where Arthur worked for a decade on a large scale irrigation project. Arthur struggled financially and it is because of Mary’s writing that the family was able to make a living.

Finally, the family would settle in Grass Valley, CA where Arthur worked for the North Star Mine. They commissioned a home (North Star House) which was built by Julia Morgan and it still standing today. Mary would continue to write until her final novel, Edith Bonham written about Helena and published in 1917.

So what was the controversy, you might ask? What did Stegner steal from Mary Hallock Foote? Thinly guised by name changes Stegner appropriates Mary’s letters (word for word!) and uses (and changes) Mary’s life story. There are noticeable changes such as the North Star House and the North Star Mine’s names being changed to Zodiac Cottage and Zodiac Mine. Then, there are the main characters who live there named Susan and Oliver Ward who are based almost entirely on the lives of Mary and Arthur Foote. As Sands Hall recalls in her article for Alta:

Mary Hallock Foote and Susan Burling Ward had far too much in common. Both were raised as Quakers in Milton, New York. Both attended Manhattan’s Cooper Union School of Design for Women in 1864. Both began their careers as illustrators, contributing to books by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Both married brilliant mining engineers, one named Arthur, the other Oliver. During their time at the New Almaden Mine in California, Mary/Susan wrote vivid letters to their dear friends Helena/Augusta, whose husbands, editors of the Century Magazine, asked to publish their correspondence, thus launching Mary/Susan’s writing careers. They went on to publish novels, story collections, and essays. Eventually, both women, each with three children, spent an achingly difficult decade outside Boise as their husbands pursued their vision of a vast irrigation system called the Big Ditch.

What’s worse is that all of the letters in the book were taken verbatim from Mary’s writing without Stegner writing any kind of citation, alerting the reader to the fact that he is using someone else’s words. At the end of his novel, Stegner only writes the following note:

My thanks to JM and her sister for the loan of their ancestors. Though I have used many details of their lives and characters, I have not hesitated to warp both personalities and events to fictional needs. This is a novel which utilizes selected facts from their real lives. It is in no sense a family history.

While Angle of Repose may not be “a family history” it is the appropriation of a family’s descendent’’ creative work. The appropriation of a woman writer who was a nationally acclaimed writer during her era.

How did this happen? Stegner was an avid scholar of the West and when he found Foote’s stories he began teaching them at Stanford. According to Hall, one of Stegner’s graduate students, George McMurry, tracked down Foote’s descendants who still lived in Grass Valley and thrilled to know academics were interested in the story of Mary Hallock Foote who’d all but been forgotten in literary history, the family shared a great deal of Foote’s materials with McMurry and Stegner.

Years passed, and George McMurry, who had been planning on using these materials to write a biography about Mary Hallock Foote, gave up on his project. But Stegner wrote to the family that while he wasn’t interested in writing a biography about Foote, he was intrigued about using some of the material to write “a big western novel of a kind…not yet seen written.” Based on Stegner’s interest, the family sent him a copy of Foote’s unpublished memoir, A Victorian gentlewoman in the far West : the reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote : Foote, Mary Hallock, 1847-1938 . At the same time, the family also sent this manuscript to the Huntington Library Press, where it was eventually published. When they share with Stegner that the memoir will be published, he responds that he thinks its a great idea that they’ll be publishing her work, but since he is so far along in his project, he doesn’t think he’ll be able to “unravel all those little threads I have so painstakingly raveled together, the real with the fictional, and replace all truth with fiction? Or does it matter to you that an occasional reader or scholar can detect the Footes behind my fictions?”

Meanwhile Stegner rushed the publication of his novel. Angle of Repose was published in 1971 and it won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972. That same year A Victorian Gentlewoman was published.

There have been numerous debates as to whether or not Stegner plagiarized Foote. To me, it seems simple. Yes, he did. And what’s worse is that he changed the story of the woman who wrote those words, transforming her strong, driven character into (as Sands Hall writes) “a griping, entitled, discontented 1950s housewife, nothing like the adventurous, deeply intelligent, resilient woman on whom she was modeled.”

That’s why it seemed obvious to me that it was necessary to write about Mary Hallock Foote in this week’s column. I hope you’ll explore some of her novels and stories (many of which are free and available online). Or, I encourage you to read Darlis Miller’s 2002 biography about her Mary Hallock Foote: Author-Illustrator of the American West.

Selected Works by Mary Hallock Foote

The Prodigal (1900)

The Desert and the Sown (1902)

A Touch of Sun and Other Stories (1903)

Royal Americans (1910)

The Valley Road (1915)

The Ground Swell (1919)

A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West The Reminiscences of Mary Hallock Foote, edited by Rodman W. Paul, ISBN 0-87328-057-1 (1972)

The Idaho Stories and Far-West Illustrations of Mary Hallock Foote, edited by Barbara Cragg, Dennis M. Walsh, and Mary Ellen Walsh. (1988)

The Little Fig-Tree Stories (1899)

The Desert and the Town (1902)

The Last Assembly Ball (1889)

A California Mining Camp (1878)

A Sea-Port on the Pacific (1878)

The Eleventh Hour (1906)

Pilgrims to Mecca (1899)

How the Pump Stopped at Morning Watch (1899)

A Diligence Journey in Mexico (1881)

From Morelia to Mexico City on Horseback (1882)

The Borrowed Shift (1898)

Sources for this article

“‘The Ways of Fiction Are Devious Indeed’” By Sands Hall

George H. McMurry Papers, Stanford Special Collections Book 4, Folders 1-5

Mary Hallock Foote: Author-Illustrator of the American West (University of Oklahoma Press, 2002) by Darlis Miller

Upcoming Events

My book tour for Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb continues in the new year. Please see below for a list of upcoming events.

January 11 - Presentation at Daughters of the Revolution, Santa Rosa Chapter

January 12, 3:30 PM - 5:00 PM - California Writers' Club Marin chapter talk on "Building a Readership with Biographer and Poet Iris Jamahl Dunkle" at Dominican University

January 15, 10:30 AM Iris Jamahl Dunkle Reading from Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb at The Century Club, SF, CA

January 24, 3:15 - 5:00 PM - A Reading with Iris Jamahl Dunkle from Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

January 25 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle Reading with Jan Beatty at White Whale Books in Pittsburgh, PA (RSVP for the in-person event) (Sign up for the Livestream)

January 27, 6:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Donovan Hohn at Literati in Ann Arbor, MI

January 28, 6:00 PM - Author Event: Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Morgenstern Books, Bloomington, Indiana

January 30, 6:00 PM - Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb with Iris Jamahl Dunkle, The Mechanics Institute, SF, 57 Post Street San Francisco, CA 94104

February

February 21, Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s talk at New York University, New York, NY

February 22, Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 23, Workshop on Erasure at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 26, 6:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at King's English, Salt Lake City, UT

February 27 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at American West Center, Salt Lake City, UT

March

March 5 - The Bill Lane Center for the American West: Stanford, CA

March 6 - UC Boulder/Center for the West, online lecture. Details coming soon!

March 13- 5:00 PM Garden City Community College, Kansas

March 14 - Books and Books in Key West, FL

March 21 - 2:00 PM New York Public Library, New York City

March 30, 4:00-5:30 PM, Occidental Center for the Arts, Occidental, CA

May

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:30 PM - National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA

I copy Linda’s utter joy at coming across your work! I write about lost and found stories, and love connecting others who share this passion.

Utterly fascinating. I knew about MHF but not the awful Stegner stuff.