Finding Lost Voices: Mary Elizabeth Jones Parish (1890 -1972) and Other Lost Voices from Tulsa, OK

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

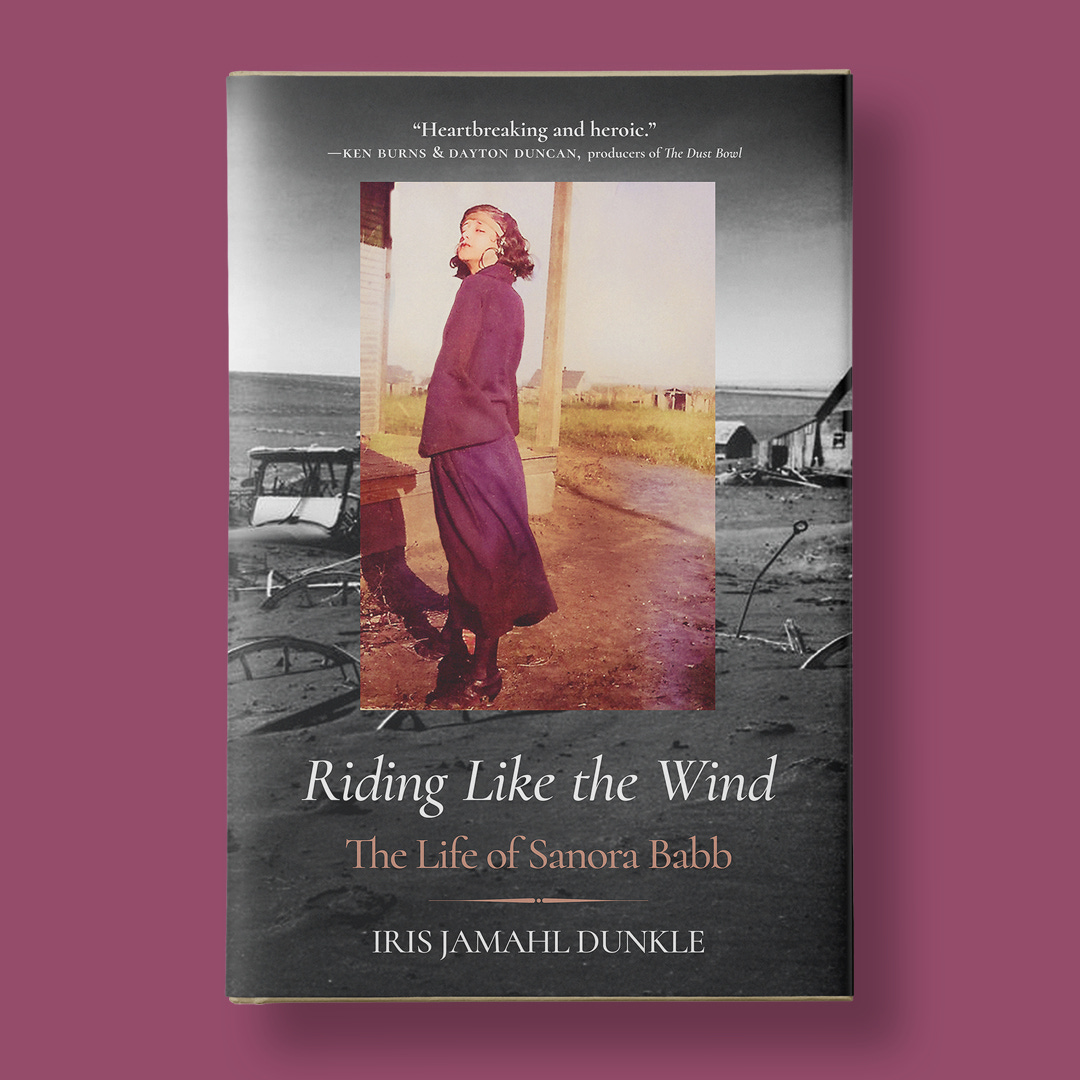

It’s been nearly a month since I launched my latest biography and this past week, I’ve been in Tulsa, OK visiting the University of Tulsa as part of my book tour for Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb. I flew to Oklahoma early on Wednesday, November 6. I’d been up most the night trying to comprehend and digest the news. In Denver, waiting for my next plane, I looked out at the snow covered landscape and felt desolate, like I didn’t understand my country anymore. That evening, though, I got to speak with a group of students, faculty and community members at the University of Tulsa about Sanora Babb’s novel, Whose Names Are Unknown and I left feeling better, feeling even more dedicated to the work I am doing in my research.

Tulsa is a city that is filled with complicated stories. It’s a palimpsest — with everything underneath showing through. Everyone I’ve met here has wanted not explain but to reveal the history of their city to me as they drove me around, or walked me through their museums, and they told it all: the good, the bad, the ugly. Somehow this openness about the brutality that America is built on, about the brutality that still pulses through her veins, made me see where we are as a nation more clearly. Made me double-down on what I am doing here.

That spirit, of telling the truth, of documenting the horror no matter the consequences is at the heart of this city. For I saw it arise again and again during my visit. At the Woodie Guthrie Center, where Sam Flowers strapped virtual reality goggles to my head so I could sit on a porch and experience a dust storm first hand. Or, where he told me about Olivia Mae Daniels, the Black woman who wrote into the radio station in California in 1937 when Woody Guthrie used a racial slur to describe Black people, an event which helped Woody Guthrie confront his own racism before he could become an activist opposed to it. A woman, whose name had been forgotten until an article was published last May called, “Woody Guthrie: Racial Transformation through the Framework of the “Long Civil Rights Movement” in the American Folk Journal.

Over dinner, an artilect from the class I taught brought up the artist and architect Adah Robinson (1882–1962), a woman whose work on Tulsa's Boston Avenue Methodist Church, an important Art Deco building erected 1924–29 was not attributed because at the time, it was thought that a woman couldn’t have designed a building of this scale.

Speaking about Sanora Babb in Oklahoma was powerful. I’m grateful to the Oklahoma Center for Humanities for bringing me here, and grateful to the engaging audience who came to the event and asked such thoughtful questions.

Yesterday before my last scheduled event, a workshop on erasure poetry I was teaching at the Carson House, I visited Greenwood Rising, a museum that honors the memory of Greenwood, or Black Wallstreet, a neighborhood in Tulsa that was decimated overnight in a massacre that took place on the night of May 31, 1921.

This three day riot began when word that a young Black man was about to be lynched for stepping on a white woman's foot. Hundreds of Black Oklahomans were murdered many of whom were buried in mass graves. The entire thriving neighborhood of Greenwood was utterly destroyed and thousands were left homeless.

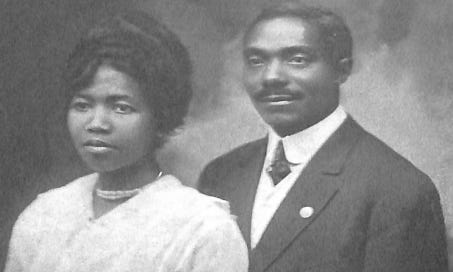

Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish (1890 -1972) was a relative newcomer to Tulsa in 1921 when this horrific event took place. But when white mobs started to gather in her neighborhood, she remembers, “I had no desire to flee…I forgot about personal safety and was seized with an uncontrollable desire to see the outcome of the fray.” And because she stayed, we were given a first-hand account of what truly happened.

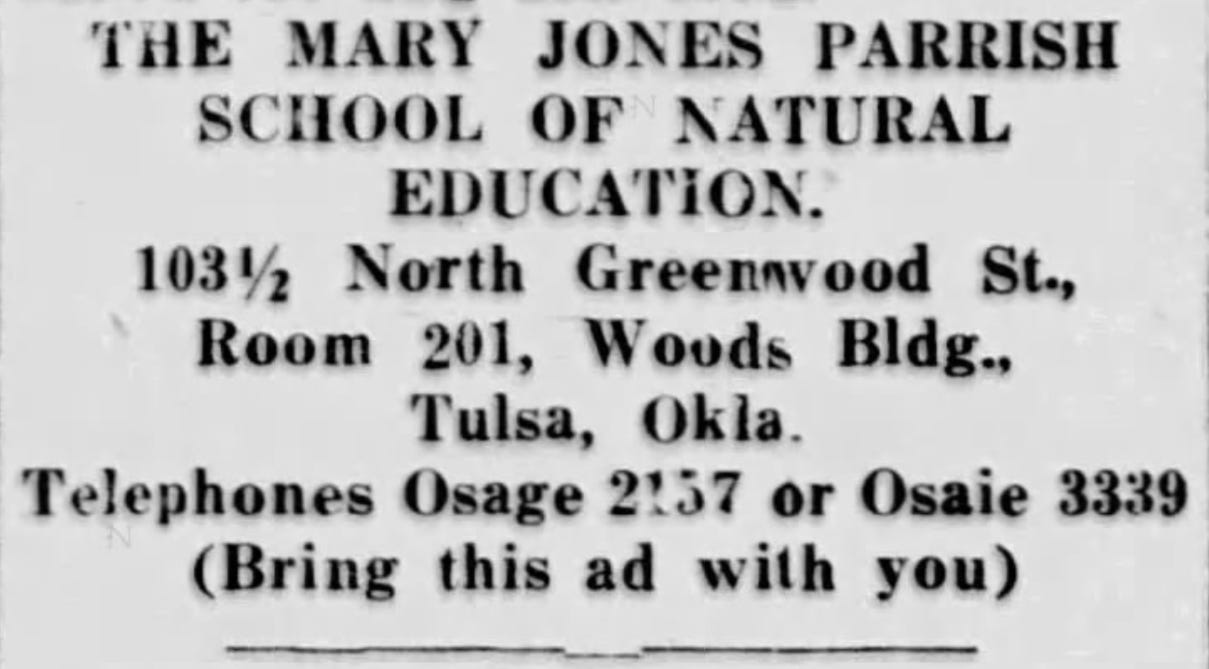

Born in Mississippi in 1890, Parrish lived briefly in the all-Black town of Boley, Oklahoma before moving to Rochester to study shorthand at the Rochester Business Institute. Parrish returned to Oklahoma to take care of her ailing mother, then after her mother’s death moved to the thriving Greenwood neighborhood in Tulsa in 1919. What she found there was a black community that was thriving, “I came not to Tulsa as many came, lured by the dream of making money and bettering myself in the financial world…but because of the wonderful co-operation I observed among our people.” Indeed Greenwood was home to a thriving community that included two movie theatres, many small businesses, a library, a hospital and a small garment factory. Parrish opened Mary Jones Parrish School of Natural Education on Greenwood avenue where she offered classes in shorthand and typing.

During the evening of May 31, Parrish was at her home, reading when her young daughter, Florence Mary, called her to the window because she saw “men with guns." Parrish was terrified, but tried to remain calm. She hid with her daughter and after a few harrowing hours, finally escaped into the night “amid a hail of bullets.” To Parrish it seemed impossible that this could be happening in Greenwood: “I had read of the Chicago riot and of the Washington trouble, but it did not seem possible that prosperous Tulsa, the city which was so peaceful and quiet that morning, could be in the thrall of a great disaster.”

Overnight, like so many other citizens of Greenwood, Parrish lost almost everything: her business, and her home, but she and her daughtered survived one of the greatest race tragedies in American history. Her friends and family urged her to leave the area, but instead, Parrish took a job with the Inter-Racial Commission collecting the stories of survivors, photographs and a “partial roster of property losses” in the Greenwood community. The pogrom had not only killed over 300 people and decimated hundreds of homes and businesses, it had also cut off the Black community’s conduits toward telling their own story. Tulsa’s two Black-owned newspapers, the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun had been destroyed and the remaining white-owned newspapers, the Tulsa World and the Tulsa Tribune would instead tell a story that blamed the Black community for the destruction of their own community.

With the help from funding from her community, Parrish published her 112-page book, Events of the Tulsa Disaster, that combined all of her research with her own eyewitness account in 1923. The book challenged the false stories Tulsa community leaders and newspapers had put forth after the event. In her account she documented how planes that circled over the Greenwood neighborhood that night had been equipped with men who were shooting riffles at fleeing citizens below. Her book also dismissed the white-owned newspaper’s narrative that the “riot” had erupted due to what had been a growing lawlessness amongst Black citizens in the city. Instead, she showed how mass-attacks like the one Greenwood faced was not a single event, but one of many that had happened across the country against Black communities during the Red Summer of 1919. Her book proposed solutions to help prevent horrific events like this from ever happening again. And she predicted what this type of violence would lead to in our future as a country, writing, “just as this horde of evil men swept down on the Colored section of Tulsa…so will they, some future day, sweep down on the homes and business places of their own race.”

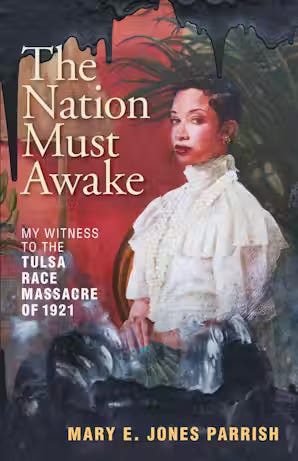

Now, over one hundred years later, Anneliese Bruner, Mary E. Jones Parrish’s great-granddaughter has reissued her great-grandmother’s book from Trinity University Press, The Nation Must Awake.

What does it mean to tell the truth in times like these? It means everything. Yesterday, after visiting the Greenwood Rising museum, I sat in a roomful of women and told the story of how I had come to write my book on Sanora Babb and how I’d used the act of erasure: of writing over the voice of John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath to empower myself to write about Sanora Babb, and the story of my family. And I listened. Each woman brought a text to talk back to: everything from Project 2025 to Cosmopolitan’s version of the Kama Sutra. When the workshop started, many of the women were filled with rage, or paralyzed with fear, or just plain sad or worried. But, by the time the workshop was over, we all felt better. Not because any thing had changed in the outside world. But because something had changed inside of us. We all felt like we could write our voices back on top of the horrific events of the past, the present and the future.

Thank you, Tulsa, for telling me these important stories. I only hope I can be as brave as people like Mary Elizabeth Jones Parrish; who instead of being paralyzed with fear, was called to action when the world around her was being destroyed. That world I saw around me at the Denver airport on Wednesday morning — that blank, and desolate looking slate —is rewritable if we bear witness.

Upcoming Events

I hope to see you at a future event!

November 13 - 6:00 - 7:00 PM - Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb - Book Club at Pasadena Heritage, Pasadena Heritage, 160 N. Oakland Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91101

November 18 - Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb - The Book Club of California | 47 Kearny Street | Suite 400 | San Francisco, CA 94108 (Attend in-person) (Attend online)

November 19, 4:30 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle in conversation with Matthew Stratton UC Davis Manetti Shrem Museum - 254 Old Davis Road, Davis, CA 95616

November 20, 5:00 PM Book Talk with Author Iris Jamahl Dunkle on “Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb” UC Berkeley, English Department (Wheeler Hall, Room 300)

November 21, 7:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle and Forrest Gander in Conversation - Clio’s Books, 353 Grand Ave, Oakland, CA 94610

December

December 1, 2:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Kristen Hanlon at the Alameda Library, Alameda, CA

December 11, 6:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Lisa Moore, Book Woman, Austin, TX

January 2025

January 24 - Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

January 25 - Reading with Jan Beatty at White Whale Books in Pittsburgh, PA

January 27 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Donovan Hohn at Literati in Ann Arbor, MI

January 28 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Morgenstern Books, Bloomington, Indiana

February

February 21, Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s talk at New York University, New York, NY

February 26, 6:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at King's English, Salt Lake City, UT

February 27 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at American West Center, Salt Lake City, UT

March

March 5 - The Bill Lane Center for the American West: Stanford, CA

March 13- 5:00 PM Garden City Community College, Kansas

March 14 - Books and Books in Key West, FL

March 21 - 2:00 PM New York Public Library, New York City

May

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:30 PM - National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA