Finding Lost Voices: Joan Vollmer (1923 - 1951), The Ghost in William S. Burroughs Queer and the new film directed by Luca Guadagnino

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

A few weeks ago, a friend and I went to a matinee of Luca Guadagnino’s new adaptation of William S. Burroughs’s novella, Queer. It’s a haunting film. Guadagnino’s reconstruction of the expat community living in Mexico City in the late 1940s and early 1950s draws you in, and Daniel Craig gives an incredible performance in Burroughs's autobiographical self-loathing role. While writing my latest biography, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb, I had to imagine Mexico City during this era when it was teeming with ex-pats (like Beat writer William S. Burroughs and leftist writer Sanora Babb). It had been extraordinary to be immersed in this setting that I had only conjured in my mind previously. But when I left the film, I felt bereft, like someone or something was missing. There was a ghost haunting the entire movie — a story I had forgotten — or, perhaps not ever fully known — whose images and facts started to surface when I left the dark theater and stood blinking under the bright sky.

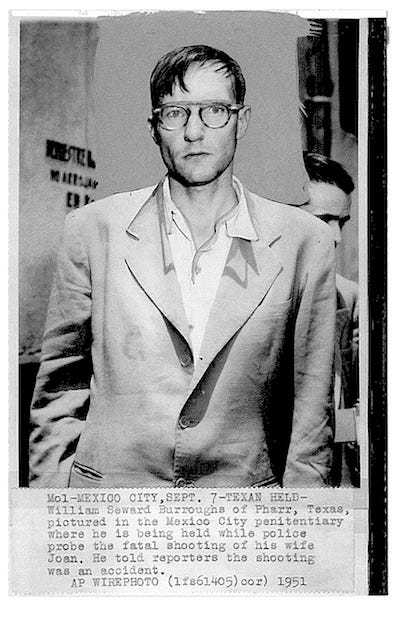

The story was one I had only ever half heard, whispered between the pages of Beat writers: the violent death of Joan Vollmer Burroughs (1923 - 1951) at the hands of her husband, William S. Burroughs, in a third-story apartment above the Bounty Bar in Mexico City while they were living there with their son (age 4) and Vollmer’s daughter (age 7). The tragic event occurred just days after Burroughs had returned from a failed quest to find Ayahuasca in the jungles of the Amazon. A trip he’d gone on with his younger male lover, Lewis Marker, left Vollmer alone to care for the children for weeks.

Burroughs had come back in a terrible state. Vollmer was worn out and upset with him for leaving her alone with the kids for so long. His lover wasn’t interested in him, and Mexico City had lost its allure. On the night of September 6, 1951, Burroughs entered the party where his lover was talking to a woman, and he wanted his attention. So he called out to his wife to say it was time for them to do their “William Tell routine.” Burroughs carried a pistol at all times in Mexico City. Vollmer drunkenly placed a highball glass on the top of her head, and an equally drunken Burroughs cocked his pistol and shot. Instead of hitting the glass, however, Burroughs shot his wife in the forehead, and she fell to the ground dead. She was twenty-eight years old.

Why did I only half know this story? Why were there only slight allusions to her death in the film and Burroughs’s novels about this period of his life (Junkie and Queer)? These questions have been haunting me since I left the theater. My pursuit to answert hem has led me to the extraordinary life of a bright, energetic young woman who greatly influenced the Beat Generation of writers: the life of Joan Vollmer Burroughs (1923 - 1951).

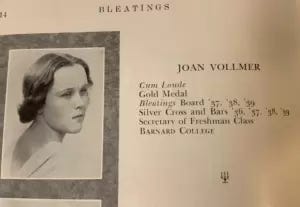

Joan Vollmer (1923 - 1951) was raised in Loudonville, a suburb of Albany, New York. She was an avid student who loved literature when she attended high school at St. Agnes School. While there, she was on the editorial board of the student publication Bleatings and received one of the school’s highest awards and was named “Most Intellectual” when she graduated in 1939. One of her articles from Bleatings survives. Initially written in French, the article was called “Les Chants Nationaux”. Here is an exert where she writes about Nazi ideology:

“The psyche of the Fascist ideology of the Nazis reveals itself in the music of Wagner. It’s not by chance that this music is Hitler’s favorite. When Hitler was rising to power/would be present, the orchestra played La Course des Valkyries. This music, with its almost hysteric heroism and its theatrical and pretentious grandeur, represents, in a symbolic way, the spirit of the Fuehrer. The music may also raises that Siegfried Rheinreise, or as banal as Over There if it takes people’s imagination, it can have a great effect on the progress of the deterioration of humanity.” —Joan Vollmer, (1939)

As her high school writing reveals, Vollmer wasn’t afraid to discuss politics (which was unusual at the time.) Vollmer wrote in her yearbook that she wanted to “to live in New York City.” A dream she fulfilled shortly after graduation when she received a scholarship to attend Barnard College, where she majored in journalism. In her first year at school, Vollmer married Paul Adams, a law student, and had her first child, Julie, in August 1944. But, reading literature opened up something in Vollmer. She read extensively and began to rebel so that by the time Paul Adams returned from the war, she had become a completely different person. A person he didn’t recognize so he divorced her.

Katie Bennett discovered half a dozen letters written by Volmer at Columbia University’s Special Collections, which offered rare glimpses of the voice of a woman whose importance had all but been erased. In her letters, Vollmer called her first husband, Paul, a “poor little soul” for believing she would change and get back together with him.

At Barnard, after her divorce, Volmer met a fellow rebel, Edie Parker and moved in with her. As Ted Morgan writes in his biography Literary Outlaw, “Edie thought Joan was the most intelligent girl she had ever met. She was independent, always questioning what anyone said, including her teachers at Barnard.” Edie also remembers how Volmer would skip class some days to sit and emerge in the bathtub reading the New York newspapers.

It was in this apartment on 118th Street in NYC that the Beat Generation was born. Lucien Carr, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac (who would later marry Edie Parker), and Vollmer’s future husband, William Burroughs, frequented their apartment and participated in all-night discussions (often led by the well-read Volmer) about social freedom and spontaneous literary composition. As Ted Morgan writes in his biography Literary Outlaw, Burroughs was enamored with Volmer: “Burroughs saw Joan as a woman of unusual insight. She was the smartest member of the group, he thought, certainly as smart as Allen [Ginsburg], in many ways smarter, because there were limits to Allen's thinking, but none to Joan's. She started Burroughs thinking in new directions.”

According to Katie Bennett, in her 2022 Lit Hub article, “On the Disappearing of Joan Vollmer Burroughs” the meetings at Vollmer’s apartment were the beginnings of the Beat Generation. The apartment is where Volmer “introduced Jack Kerouac to Marcel Proust and William Burroughs to the Mayan Codices…. The Beat Generation was as much a cultural movement as a literary one, and through her sexual fluidity and refusal to submit to socially prescribed female timidity, Joan inspired women to become “Beat.” Given her essential role in the beginnings of the Beats, why isn’t Vollmer’s name remembered? Partially because she was written off as a drug addict (but which Beat writer wasn’t a drug addict?)

At these Beat gatherings, everyone started taking Benzedrine, an amphetamine that fueled their late-night talks. Jack Kerouac supposedly introduced Vollmer to the drug, which she took liberally. In 1946, she was hospitalized for being high on Benzedrine and having psychotic episodes. In her letters, she wrote about how she had to convince the attendants at Bellevue Hospital that she “wasn’t completely mad” so that her daughter wouldn’t be taken away from her.

In the spring of 1946, Burroughs, who had become addicted to heroin, was arrested for forging a narcotics prescription. Vollmer arranged to have her psychiatrist sign a surety bond for Burroughs's release, which required him to return to his home in St. Louis to live under his parents' care. Afterward, Burroughs returned to New York City to tell Volmer he wanted to marry her. (Though two would never officially be married.) Vollmer and her daughter would move to a farm in New Waverly Texas, that Burroughs had purchased with family money. They planned to grow marijuana and live a quiet life on a rural farm. Vollmer loved to swim with her daughter in the river. Soon, she became pregnant with her son, who was born in 1947. When Burroughs got in trouble with the law in Texas, they moved to New Orleans, where the police pulled over Burroughs, and it was discovered he was carrying an unregistered handgun. When the police searched Burroughs’s home, they found his stash of heroin and half a dozen or more firearms. To avoid arrest and imprisonment, Burroughs fled to Mexico City, and Vollmer and the children followed soon after. They arrived in Mexico City in 1949. Two years later, Vollmer would be dead. Her husband would only serve thirteen days in prison for killing her. Her children would be sent elsewhere to be raised by grandparents, and her body would be buried and left for decades in an unmarked grave in Mexico City. (Her name was added more recently).

And because she was only twenty-eight and had spent seven years of her life as a mother of young children, there is little record of her literary output. But judging by her letters, her lack of literary output is our loss.

In the introduction to Queer, written when the novella was finally published in 1985, Burroughs writes he couldn’t make himself reread the manuscript. “The book is motivated and formed by an event which is never mentioned, in fact, is carefully avoided: the accidental shooting death of my wife, Joan, in September 1951.” Later in the same introduction, Burroughs explains, “I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to realize the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.”

When I walked out of the theater a few weeks ago, it was not just the tragic story of Joan Vollmer’s death that was haunting me. Nor was it the fact that her husband murdered her. It was that after her death, her whole life was erased. What I was sensing was the lack of the story. The way her husband had used her death as part of his mysterious, cowboy-junkie persona to fuel his literary career.

Selected Sources:

“On the Disappearing of Joan Vollmer Burroughs” by Katie Bennett

“The dark side of William Burroughs, wife killer behind Daniel Craig’s Queer” by Nick Hilden

“The Doane Stuart School’s Beat Generation Connection”

Breaking the Rule of Cool: Interviewing and Reading Women Beat Writers by Nancy M. Grace and Ronna C. Johnson

The Birth of the Beat Generation: Visionaries, Rebels, and Hipsters Steve Watson

Queer by William S. Burroughs

Junkie by William S. Burroughs

Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs

Upcoming Readings

January 24, 3:15 - 5:00 PM - A Reading with Iris Jamahl Dunkle from Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

January 25 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle Reading with Jan Beatty at White Whale Books in Pittsburgh, PA (RSVP for the in-person event) (Sign up for the Livestream)

January 27, 6:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Donovan Hohn at Literati in Ann Arbor, MI

January 28, 6:00 PM - Author Event: Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Morgenstern Books, Bloomington, Indiana

January 30, 6:00 PM - Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb with Iris Jamahl Dunkle, The Mechanics Institute, SF, 57 Post Street San Francisco, CA 94104

February

February 21, 2:00 PM EST, Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s talk at New York University, New York, NY

February 22, 5:00 PM, An Evening with Iris Jamahl Dunkle at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 23, 10:30 AM - 2:30 PM Workshop on Erasure at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 26, 6:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at King's English, Salt Lake City, UT

February 27, 3:30-5 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at American West Center, LNCO 2110, Salt Lake City, UT

March

March 5, 4:30 - 6:00 PM- Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Gavin Jones at The Bill Lane Center for the American West: Stanford, CA

March 6 - UC Boulder/Center for the West, online lecture. Details are coming soon!

March 13- 5:00 PM Garden City Community College, Kansas

March 14 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Books and Books in Key West, FL

March 21 - 2:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the New York Public Library, New York City

March 30, 4:00-5:30 PM, Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the Occidental Center for the Arts, Occidental, CA

May

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA

I am hearing so many stories of male popular writers and the like who have essentially stolen the life and creative works of the women around them. To put focus on these women is a necessary act in reclaiming history for all women.

An almost forgotten powerhouse, rewritten as a behind the scenes figure, relegated to a footnote. A recurring theme that always ends up being the woman.