Finding Lost Voices: In the Garden of Anne Spencer

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

This week’s post is brief as the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference has just begun and I’m busy working as the poetry and translation Director. But, I wanted to at least post a brief post and share with you information about how to attend the public readings at the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference in case you are in the Bay Area.

I’ve never been much of a gardener. But this morning, as I listened to Camille Dungy talk about her garden in a conversation about her fascinating nonfiction book, Soil, I was so inspired that I started to believe I could be. Her discussion with Helena de Groot on the podcast Poetry Off the Shelf delved deep into how she came into creating her own garden and introduced one of her literary foremother’s gardens: the poet Anne Spencer (1882-1975). Spencer was a well-published poet associated with the Harlem Renaissance, even though she lived far away from Harlem in Lynchburg, Virginia. She was also a civil rights advocate, teacher, librarian, wife, mother, and, as Dungy pointed out, a gardener.

Spencer was born Anne Bethel Scales Bannister on February 6, 1882, on a plantation in Henry County, Virginia. Both of her parents were of mixed lineage. Her father, born a slave in Henry County in 1862, was of black, white, and Seminole Indian ancestry. Her mother was born about 1866 on the Rock Spring Plantation in Critz, Virginia. According to Spencer's biographer J. Lee Greene, Sarah Louise Scales’ mother was a former slave, and her father was a wealthy Virginia tobacco family member. Soon after Spencer was born, her family moved to Martinsville, where her father opened a saloon. Within a few years, her parents separated, and her mother took Spencer to Bramwell, West Virginia, where she placed her in the foster care of William Dixie and his wife, a prominent black couple so that Sarah Scales could work full-time.

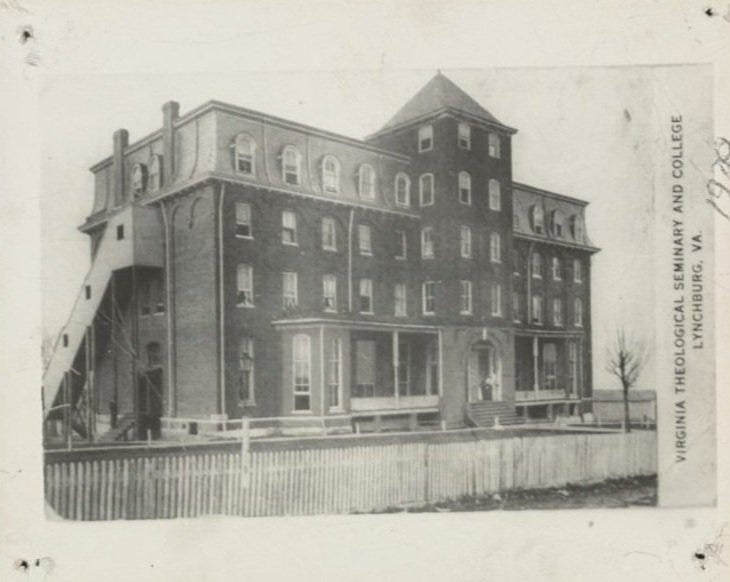

Spencer’s parents wanted her to receive a proper education, not in the inferior segregated public schools in West Virginia but in a relatively new preparatory and college institution for African Americans. In 1893, Scales brought Spencer to Lynchburg to attend the Virginia Theological Seminary and College, pretending that the eleven-year-old who had never attended school was already twelve and literate. The school was a pioneering Black College, offering an equal curriculum despite its board’s patronizing view that occupational training and literacy were enough. Spencer thrived during her education, and though she arrived at the school barely literate, when she graduated six years later in 1899, she delivered the valedictory address.

Spencer married Edward Alexander Spencer in 1901, and they had three children. Her husband designed and built their Queen Anne-style home at 1313 Pierce Street in Lynchburg. Spencer would remain in Lynchburg for the rest of her life. The house was on a large plot, and Spencer planted a large flower garden on it. Also in the backyard was her writing studio, which she called Edankraal (a combination of Anne's and Edward's first names with the suffix—kraal, which in Afrikaans means corral).

Spencer began writing poetry at a young age while attending the Virginia Theological Seminary and College, but her work wasn’t published until she was in her forties. In 1919, she and her husband established a local chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). When they hosted an NAACP meeting at their home, the writer and activist James Weldon Johnson stayed with them, and while he was standing in their kitchen, he noticed Spencer’s poems hanging on the walls. He was so impressed that he had her poem, “Before the Feast at Shushan,” published in Crisis in February 1920.

During her lifetime, Spencer would publish more than thirty poems in anthologies, including Johnson’s, The Book of American Negro Poetry (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922); Countee Cullen’s Caroling Dusk (Harper & Brothers, 1927); and Alain Locke’s The New Negro, as well as in Opportunity and Crisis magazines but she never published a collection, and she was often frustrated by editors and publishers who censored or misunderstood her work. She composed her work slowly, letting the poem sit and germinate in her head. She explained, “I might have an idea for a poem in my head for a long time before something happens to cause me to write that idea down” (Greene 148).

The garden was often at the heart of her work. She used flora to illustrate racial and feminist themes in poems that still feel modern today.

Lines to a Nasturtium (A Lover Muses)

Flame-flower, Day-torch, Mauna Loa,

I saw a daring bee, today, pause, and soar,

Into your flaming heart;

Then did I hear crisp, crinkled laughter

As the furies after tore him apart?

A bird, next, small and humming,

Looked into your startled depths and fled . . .

Surely, some dread sight, and dafter

Than human eyes as mine can see,

Set the stricken air waves drumming

In his flight.

Day-torch, Flame-flower, cool-hot Beauty,

I cannot see, I cannot hear your flutey;

Voice lure your loving swain,

But I know one other to whom you are in beauty

Born in vain:

Hair like the setting sun,

Her eyes a rising star,

Motions gracious as reeds by Babylon, bar

All your competing;

Hands like, how like, brown lilies sweet,

Cloth of gold were fair enough to touch her feet.

Ah, how the sense reels at my repeating,

As once in her fire-lit heart I felt the furies

Beating, beating.

I may never plant a garden like Anne Spencer or Camille Dungy, but the idea that a garden empowered these writers to forge their creative paths certainly makes me want to try!

To read more of Anne Spencer’s poetry visit: https://poets.org/poet/anne-spencer

Napa Valley Writers’ Conference

This week, I’ll be at the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference in Napa, CA. For those who are local, I hope you’ll stop by! All events take place at 2277 Napa Vallejo Hwy, Napa, CA 94558, except for Tuesday’s evening event, which will be held at Silverado Winery.

EVENING READINGS (Performing Arts Center, Napa Campus, Napa Valley College)

Sunday, July 21, 6:30 pm – Bruce Snider & Jamil Jan Kochai

Monday, July 22, 6:30 pm – Jane Hirshfield & Peter Ho Davies

Tuesday, July 23, 6:30 pm – Jan Beatty & Lysley Tenorio (reading takes place at Silverado Vineyards)

Wednesday, July 24, 5:30 pm – C. Dale Young & Lan Samantha Chang

Thursday, July 25, 6:30 pm – Emily Wilson & featured participants

DAILY CRAFT TALKS (Performing Arts Center, Napa Campus, Napa Valley College)

Monday, July 22:

9 am – C. Dale Young – “Doubt and Uncertainty: The Adverbial Gesture as Rhetorical Strategy”

1:30 pm – Lan Samantha Chang – “Scope and Scale in the Novel and Short Story”

3 pm – Emily Wilson – “Re-translation, Why and How?”

Tuesday, July 23:

9 am – Bruce Snider – “SESTINAMERICA: Poetic Form in the Age of Trump”

1:30 pm – Jamil Jan Kochai – “Showing through Telling”

Wednesday July 24:

9 am – Jane Hirshfield – “Past? Present? Future? Verb Tense As Life Sense”

1:30 pm – Peter Ho Davies – “Truth or (Auto)Fiction?”

Thursday, July 25:

9 am – Jan Beatty – “The Beauty of Collision”

1:30 pm – Lysley Tenorio – “And Then We Came to the End: Notes on Endings.”

Friday, July 26:

9 am – First Books Panels in Fiction and Poetry – Please check back for locations

Don’t miss our free FREE DROP-IN COMMUNITY CLASSES (Community room, McCarthy Library, Napa Campus, Napa Valley College)

Monday, July 22 – Friday, July 26 Poetry Encounter with Maw Shein Win 10:30 am

Monday, July 22 – Thursday, July 25: Guided Reading Class with Caroline Goodwin 4:30 pm

Upcoming Readings

July 27, 1 - 3 PM PST - Poets in Parks featuring Jan Beatty, Iris Jamahl Dunkle, Forrest Gander, Dana Gioia, Brian Martens and Katie Peterson

Armstrong Redwoods Forest Theater

17000 Armstrong Woods Road

GUERNEVILLE, CA 95446