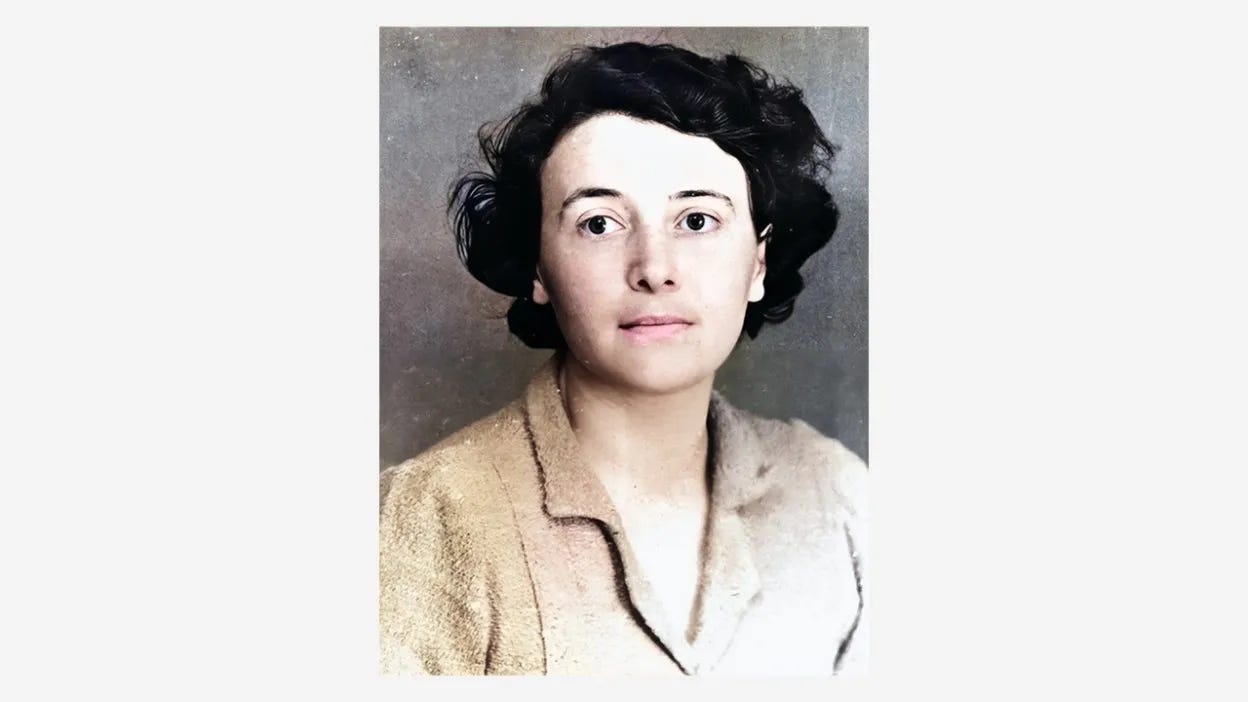

Finding Lost Voices: Eileen Blair (1905 - 1945), who helped write Animal Farm, Wifedom, and an Interview with Australian author Anna Funder

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

Welcome to the latest issue of Finding Lost Voices. I want to begin this week’s post with a thank you to all who have become paid subscribers. I appreciate your support as I transition into my next research project — writing my book Strong about the history of strong-bodied women in the United States from the late 1800s to the present. This work requires travel to research collections, and your subscription to this blog supports that research. If you’ve enjoyed these posts and have the means, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

As most of you know, I’ve been on tour for my latest book, Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb, for the last few months. On tour, one of the most common reactions I get from the audiences I speak to is surprise that John Steinbeck appropriated content from Sanora Babb and got away with it. My audiences don’t realize how common it is for male authors to appropriate material from women, and nowhere is this theft more common than in a marriage. I learned much about this when I wrote my biography: Charmian Kittredge London: Trailblazer, Author, Adventurer. Charmian, a college-educated writer before she met Jack London, helped write many of his books, including The Valley of the Moon. I learned how common it was for the wives of famous authors to have helped write their books and then have their authorship erased or maligned by future biographers. That’s why when I first came across Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life by Australian author Anna Funder (1905 - 1945), I was not surprised to learn that Eileen Blair, the wife of George Orwell, had played an integral role in the writing of his classic novel, Animal Farm. Past scholars completely ignored her contribution, and her life had been systematically erased. What’s striking about Funder’s stunning biography is how she discusses why this theft occurred, how erasure occurred, and how the work of women remains unacknowledged in the present. For this week’s post, I’ll be talking about the life of Eileen Blair and showcasing an interview I had with Anna Funder about her important work.

Eileen O'Shaughnessy was born in the northeast of England in September 1905. She studied English on scholarship at Hughes College at Oxford. In 1934, she wrote a dystopian poem, “End of the Century, 1984” (which may have influenced her future husband, George Orwell’s novel). That same year, she enrolled in a master’s program at University College, London, where she studied Psychology. She met Eric Blair (AKA George Orwell) in the spring of 1935, and the two got married in 1936. Eileen traveled to Spain during the Civil War, where she actively worked in the office of the Independent Labour Party. But, when her time in Spain is later recounted in her husband’s account, Homage to Catalonia, her active role is greatly diminished. This is just one of the periods of Eileen’s life that has been erased and that Funder so carefully recreates in her marvelous book, Wifedom.

At the beginning of World War II, Eileen supported her and Eric by working in London at the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information n. For years, Eileen had suffered from uterine tumors, and in 1945, she went in for a hysterectomy, from which she never returned. I learned so much about Eileen from Funder’s book (which will be released in paperback in the US on February 25th). What follows is the conversation we had last weekend about Eileen Blair and Funder’s approach to writing about her life.

Iris Jamahl Dunkle: First, could you tell us about Eileen? How did you discover her? What is it about her that made you want to write this book?

Anna Funder: Well, I discovered Eileen after I spent a summer rereading George Orwell, I found myself kind of feeling, in retrospect, overburdened by what I now call wifedom, which were all of the unspoken expectations on me to be looking after family, members, and house, and everything else so sort of multi-generations and in every direction. And so I was then a perimenopausal white woman in a wealthy country, married to a nice guy, and then just thought to myself. Why is it that all of this work is falling to me? Nobody is asking me, and yet the expectations are firmly there because of my gender that I will do all of this work of life and love. And I think, instead of getting therapy… I started rereading Orwell. I've always been interested in systems of power, how they work, and who they work on, and I think, subconsciously, I found myself, albeit a very privileged white person. Still, on the wrong end of a power system, and you know, my mother was a feminist, intellectual psychologist. You would have thought I had a lot of equipment to deal with this. And yet that was the situation. So, I started rereading Orwell because he writes well about systems of power from an underdog point of view, and I thought maybe there’d be something in there that is enlightening for me. I read my way through his work. And then these six biographies of him, the significant biographies, all written by men, but after that, I was still not cured. So I was looking around on the Internet and found these letters from his 1st wife, Eileen, to her best friend Nora, which were discovered in 200 (after those biographies were all written) and in the first of those (letters) Eileen is writing to her best friend from her time at Oxford when she was reading English under J.R.R. Tolkien …and she writes to Nora, it's six months after she married Orwell, and she writes to Nora, I'm sorry it's taken me so long to write to you, but we have quarreled so continuously and bitterly since the wedding that I thought I'd just write one letter to everyone once the murder or separation was accomplished.

So this is hilarious and also serious, because, as women and as writers, we both write and read between the lines, and I just thought, why does she want to kill him even in jest? And what are they fighting about? She's an independent woman studying for a master's in psychology and has been running her own life…for 9 years since she came down from Oxford. What are they arguing about as she gets used to this new role of wife? And I turn back to the biographies, to the point where they're writing about Orwell's newlywed days, and they write things like Orwell was never happier before or since he became a newlywed, the conditions were idyllic for him. And I just thought, Wow, that passive voice. Someone is making those conditions. And she has been erased by grammar in the center. She's been erased by the biographer, and she's been erased by history. I'm going to go and find out who she is.

Iris Dunkle: I love that. And I love the way that you call out those biographers for their misogyny. I'd love for you to talk more about whether that erasure was it that erasure is what fueled you toward the counter-narratives you create in your book. Because I mean, you didn't approach this as a project of simply writing a biography about Eileen. Right? So why did you choose to write a counter-narrative?

Anna Funder: In Wifedom, I look very closely at both the micro methods of erasure of women on the line in Orwell's work and in the biographers and sort of at the more macro. So why don’t we give women as mothers, wives, mentors, patrons, lovers, lifesavers, rescuers--people who make life possible for these men--credit? So, looking at the micro level, things like conditions were idyllic, the visas were obtained, the manuscript was typed, and so on. The passive voice is a very common and effective quick and dirty way of erasing what a woman does because it's a way of saying something happened without telling us who made it happen. And once you start reading like that, you see that everywhere. What it adds up to is a giant fiction. …A biography is ostensibly a nonfiction form. So, the biographers try to stick to the facts about Orwell's life. But if you leave out the women who made things possible, brought him up, and made his life's work possible, you're telling a fictional story by omission. So it seemed to me that in order to put all of those women back in, I had to work in two modes: one was nonfiction mode, where I’m very careful of my sources (I have 400 end notes) You can't take on Orwell, and the enormous Orwell Fan Club/ Industry that exists out there, which is very gendered male, without being sure of your sources and facts. So, I tie everything in. And there's a nonfiction narrative that says this is how things were. But this is how they've been told to us, and in that gap live these women. There's also a lot of evidence of her voice from Eileen. There are these marvelous letters, not just the six new ones I got permission to use. They date from the beginning of the marriage-- the murder or separation letter--right to the end of the marriage to these very poignant, tragic letters that she writes that are very revealing about her marriage. No one has given them the kind of attention that I felt they deserved. I reproduce those letters in fictional scenes in which Eileen is writing them in the book. So that is a counter-fiction story in which I'm trying to bring her back to life. I'm a fiction writer. I write novels, and I felt like that was a way of ensuring she lived in the reader's imagination. I could have written a novel; it would have been much more manageable. But I wanted this book to be an intervention in history because history has been written in a partial way in both senses of the word. We only see part of it, essentially the part that privileges the man, as if he did all his work alone, and no woman was harmed in the making of it. So that's why the book has the structure and the breadth that it has. I think the word counter fiction is there because it highlights that the narratives that come down to us of men's lives are fiction in which it looks like they did everything alone and unaided.

Iris Jamahl Dunkle: Your answer brings me to my next question: I love the structure of this book. It highlights to me how one sometimes has to move away from the traditional form of biography when we are writing about women who have been erased. I loved the way your present-tense voice inserts itself. Can you discuss how and why you decided to insert your personal experiences into this book?

Anna Funder: The reason for couching this narrative with a present tense of my life, which is not hugely representative or indicative, or anything, is because I’m not just looking in both forensic and emotional and intellectual way at this marriage of eighty years ago. I’m also asking why this dynamic of a woman’s work is indispensable and invisible rings so true to me today. My perspective comes from being a novelist. You're always picking the detail that is most telling. And so there were details in my and my friends' lives that show this issue is alive and well today. The UN estimates that if the unpaid work of women, which is happening across the planet in every society, had to be paid for, it would cost 10.9 trillion US Dollars every year. This means that the work that women do to sustain families, communities, societies, and nations, both economically, physically, emotionally, and psychologically, is indispensable, but also unaffordable. The interesting thing is that it is so essential; how can it be invisible?

Orwell was very interested in decency: what it is to be a decent human being, what it is to be a respectable man, and his interest in decency, which is what, for instance, the Orwell fans so adore, comes from a place where he's worried that he's not a decent man, and he meant that in terms of not being heterosexual which I think he was very worried about. He was a deeply repressed homosexual by many accounts, but also, he meant it in terms of integrity, you know, being the same inside and out, and we are all interested in that. The fact that I'm not interested in saying, oh, here is this complicated man who wasn't what he said he was. That's a simplistic zero-sum game, cancellation-culture discourse, which doesn't interest me at all. It is much more interesting to look at the complexities of a man out of whom 1984 came, which is brilliant and important. We need it now more than ever. But it’s also sadistic, paranoid, misogynist, and so on. That's not coming out of a man who's a straightforward fellow, a decent everyman, that's coming out of a complex man who can see these things in himself and then projects a world in fiction in which they exist.

I wanted to show today, how I feel in my life. I'm in my late fifties. Those sorts of erasures have happened; I’m not coming at this from a flawless point of view. I'm coming out of this from my complexities and wanted to reveal some of those flaws. I wanted to make it personal for all readers today, just to say, this is not about a marriage eighty years ago. This is about gender relations, now. Things in the rearview mirror are closer than they appear.

Iris Jamahl Dunkle: Can you talk more about how you suggest that Eileen greatly influenced George Orwell’s Animal Farm? I love how you develop this influence throughout the text (her tending to the animals they keep and her wit).

Anna Funder: When Orwell says to Eileen, I want to write an essay critical of Stalin, she says that will never be published, so… they write a satirical novel instead, this woman who studied under Tolkien, who understands animal stories, who understands fable structure, who has enormous wit, who wanted to write a book with all the hens at Wallington in the decrepit cottage that they to live in as characters, and they end up writing Animal Farm. Eileen works to support them at the Ministry of Food, and he works each day, and then she comes home at night, having shopped for dinner, cooked dinner for whoever's been bombed out, and staying. Then she ends up washing up at midnight. Then they get into bed together and go over what he's done every night, and then we know this because she comes back in to work and regales her colleagues with this. One of her colleagues was a novelist named Lettice Cooper, who wrote about Eileen in her novel, Black Bethlehem (1947). She also wrote an essay about Eileen where she discussed this time period. Eileen was enormously excited about this book and thought it was a total winner. Orwell thought Animal Farm was his best work, and it is a complete outlier in tone, language, structure, and perfection compared to all of his other work. All of his other work effectively has an Orwell stand-in character, who is a kind of underdog everyman: Winston Smith, Gordon Comstock, John Florey, and so on. So we see things through the point of view of this Orwellian, you know, decent, underdog person, whereas Animal Farm is an ensemble cast of characters, including female characters who are very well written. It's not sadistic. It's not brutal. It's not paranoid. It's very acutely aware of this allegory of Stalinist power that is being written. So. yeah, it's utterly clear that she was very involved in that work. And, in fact, when you read her letters, you see the same sorts of observations of character and the same wit in language and humor that he wasn't able to summon in of any of his other work. She died before it was published, very sadly, because I think it gave her a lot of pleasure to do that with him. He said, and this is another example of a kind of swift and dirty patriarchal mechanism of erasure of women, to a female friend in a letter that it was a shame that Eileen didn't live to see the publication of Animal Farm, because she even helped in the planning of it. That was too much for one of the biographers who just deleted the “even” from that quote because obviously, her contribution was so much more, that to deny it and trivialize it so vehemently looks like a bastard act, and that's then incompatible with the biographer's image of Orwell. So I feel for the biographers. Human beings are complicated, and they love him as an author, so they want to love him as a person. But we love work that is difficult. We love work that is scary. We love work that shows us things that we don't normally want to see, and puts them safely between covers you know, but that the person who has seen those things has been there in their mind.

Iris Jamahl Dunkle: Thank you Anna for this wonderful conversation and for your incredible book. To read Anna Funder’s amazing new book, Wifedom, visit.

Upcoming Readings

I hope to see you all at some of my upcoming events!

February

February 21, 2:00 PM EST, Iris Jamahl Dunkle’s talk on the Craft of Biography at New York University, New York, NY

February 22, 5:00 PM, An Evening with Iris Jamahl Dunkle at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 23, 10:00 AM - 2:00 PM - WORKSHOP Empowering Your Voice Through Multimedia Erasure at North Bay Letter Press, Sebastopol, CA

February 26, 6:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at King's English, Salt Lake City, UT

February 27, 3:30-5 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at American West Center, LNCO 2110, Salt Lake City, UT

March

March 5, 4:30 - 6:00 PM- Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with Gavin Jones at The Bill Lane Center for the American West: Stanford, CA

March 6 - UC Boulder/Center for the West, online lecture. Details are coming soon!

March 13- 5:00 PM Garden City Community College, Kansas

March 14 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Books and Books in Key West, FL

March 21 - 2:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the New York Public Library, New York City

March 30, 4:00-5:30 PM, Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the Occidental Center for the Arts, Occidental, CA

April

April 12 - 3:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at Full Circle Bookstore, Oklahoma City.

May

May 17 - 5:30 - 7:30 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle at the National Steinbeck Center, Salinas, CA

Thank you. I read this book with a boiling rage. So glad to have Eileen's life put into the history of Orwell and his writing.

Amazing interview! I never tought about how the passive voice really erases women's work, so interesting, now I will really see this in everything. Thanks for that!