Finding Lost Voices: Clara Shortridge Foltz (1849 – 1934) The First Female Lawyer on the West Coast

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered.

One of the beautiful things about writing this column is how people come to me with stories about the lost voices they have discovered. Last week, Kathryn E. Meola (who is a Senior Partner & Partner-in-Charge at Atkinson, Andelson, Loya, Ruud & Romo) shared the story of Clara Shortridge Foltz (1849 – 1934), the first female lawyer on the West Coast who pioneered the idea of the public defender’s office. Meola had written an article about her and shared it with me, and she joined me for an interview where we discussed Foltz’s life, what it is like to be a woman practicing law, what it means to have foremothers, and what it means to have a female attorney running for the office of president.

Clara Shortridge Foltz was born in Milton, Indiana, in 1849. She was educated at a co-educational school in Iowa. In 1864, at age fifteen, she eloped with Jeremiah D. Foltz. As Kathryn Meola writes, “In the early 1870s, the Foltzes, Clara’s parents, and her four brothers migrated first to Oregon and then to California, settling in San Jose, where Clara and Jeremiah had their fifth child. They arrived amid a severe economic depression, and Jeremiah Foltz, a poor provider in the best of times, made matters worse by frequent trips to Portland to visit the woman who ultimately became his second wife. The Foltzes were divorced in 1879.”

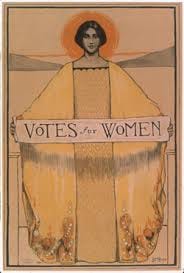

But Foltz wasn’t stymied by her fate. She had fortitude and, thanks to her forward-thinking parents, an education. According to her biographer, Barbara Allen Babcock, when she was a child, Foltz dreamed of becoming an orator, of fame, of “political recognition.” So, Foltz followed her dreams and began giving public talks. Her topic was women’s suffrage, and as Meola states, “Her dramatic gifts, passionate sincerity, and the still-novel sight of a woman lecturer all brought her some early success.” (Foltz would go on to author the Women’s Vote Amendment for California that passed in 1911).

Through her association with suffragists, Foltz found entry into the field of law. The suffragist Sarah Knox-Goodrich connected her with a local judge with whom she began studying law and continued studying with her father. Before she could become a practicing lawyer, however, several hurdles stood in her way. First, she was the first woman to try and pursue a career in law in California so there was no path to follow. At the time, no women were practicing law on the West Coast. Second, a California code provision limited law practice to white males. But these hurdles didn’t stop Foltz. Foltz authored the "Woman Lawyer Bill," in which she replaced the words "white male" with "person." As Meola recounts, “Joined by a small band of sister suffragists, Foltz lobbied her Woman Lawyer’s Bill through the legislature. The bill passed by two votes, with a final count of 37 to 35 on March 29, 1878.” Even though the bill passed, it wouldn’t be finalized unless Governor William Irwin signed it by midnight on April 1, 1878. Once again, Foltz was “unwilling to give up.” Instead, she went to the capital, “slipped past two guards” and “entered Governor Irwin’s office” unannounced. In that room, she used the oratory skills she’d been honing while on the speaking circuit. Somehow, she persuaded the governor “to sign before the pending midnight deadline.” That Fall, Foltz passed the examination, and by doing so, she became the first woman admitted to the California bar.

Though she could practice law, it bothered Foltz that neither she nor any other woman could study law formally. So, she and her friend and ally, Laura de Force Gordon, paid $10 to apply to Hastings College of Law. As Meola explains, “The women were permitted to enroll and attend but not allowed to stay more than a few days. At the end of the third day, Foltz received a letter from the registrar dated January 10, 1879, informing her that the directors had ‘resolved not to admit women to the Law School.’” What was the reason why they were no longer admitted? According to an article in the San Francisco Chronicle, they could no longer attend because the male students found their presence too distracting. One key issue was the noise the women’s petticoats made during class.

Foltz and de Force Gordon sued the college, embarking on a long and costly legal battle they ultimately won. Unfortunately, by that time, they could no longer afford to attend the college, and neither obtained a law degree. (In 1991, female students lobbied the administration to correct this error, and Hastings College of the Law finally granted Foltz a posthumous degree of Doctor of Law.)

Meola explains, “The Hastings Trustees argued that women should never be lawyers – that the study of law was not proper for women. They claimed that studying law would make women less womanly, and thus destroy the home. They also stated, “The peculiar qualities of womanhood, its gentle graces, its purity, its delicacy, its emotional impulses makes law unfit for women.” Clara’s rebuttal was not only brilliant but demonstrated why she was known as a great orator:

‘claiming that broader education would make women less womanly and thus destroy our homes – that is not the legitimate effect of knowledge of any kind. On the contrary, a knowledge of law of our land will make women better mothers, better wives, and better citizens.’”

Foltz went on to practice law for the next fifty years, often being the only woman in the courtroom. She was dedicated to making the path easier for women to become lawyers and often taught law at her office to aspiring female lawyers. In 1893, she founded the Portia Law Club in San Francisco, which prepared women for the bar.

Part 2: An Interview with Kathryn E. Meola about Finding a Foremother in Clara Shortridge Foltz

Dunkle: What were you drawn to telling the story of Clara Shortridge Foltz and how did you discover her?

Meola: We have written bios of notable women in history for Women's History Month at the firm. When I discovered that Foltz was the first female attorney in California, I wanted to write about her. She really resonated with me for two reasons: because she had a nontraditional path to the practice of law and because, at each stage of her career, she lifted up others to provide the education that they might need so that they could be successful.

Dunkle: Do you feel like you had many female role models as a woman lawyer when you attended into law school and began practicing law?

Meola: Not exactly. When I went to law school at the University of San Diego, my trial skills class professor shared stories about what it was like to be a practicing lawyer as a woman. She said that within her career, there were many times when she would be in chambers with a judge, and a judge would say something like, we can settle this case right now on that couch over there. It was stories like that that made me angry.

I've been practicing for more than 30 years now, and the number of women in the profession has changed over time. Now there are more women attorneys admitted to the bar, but we aren’t in the upper echelons of the law firms. There's still a long way to go.

Dunkle: How did you first come across her story?

Meola: I Googled, ‘notable female lawyers’, and she came up as the first female lawyer. When I read her story, what struck me was how, when people tried to keep her out of the profession, she was actually able to pass a statute that became a constitutional amendment about not discriminating against a person's sex, but also, you know, creed and ethnic and racial discrimination as well. Then, even after she's practicing law and is a successful lawyer in her own right, she still regrets she didn't have this traditional education and when she tries to get into Hastings College of Law she's only admitted for a day before her and her friend, you know, are told that she's they're too much of a distraction.

Dunkle: Those petticoats!

Meola: Yes! It's just mind-boggling that that's the reason they were given for being too much of a distraction, even though she was a successful lawyer at that point. Then, the heartbreak was that she couldn’t attend Hastings once they won their case, which had to go up to the California Supreme Court, which cost money and a lot of time. I mean, years, right? They won their case at the top level. They couldn't complete their education because of losing the money to pay for it.

Dunkle: That was so sad to hear at the end of that story. It's just such an astounding thing how women of that era fought for their rights. They had no right to vote. Yet they were doing these incredible things, like the fact that she was a suffragist and putting everything on the line for that at the same time as she's a single mom. You can imagine the fortitude she had. She must have just been such a driven character. Don't you think?

Meola: Despite the challenges in front of her, she either went over them or around them. And that's the piece that spoke to me because you may not reach that higher echelon at the firm that you've chosen initially, so you might have to move, right? You might have a different path than you envisioned in the first place. But if you keep fighting for it just like she did, you can achieve what you want.

Dunkle: What else would you like to share about Foltz’s life with us?

Meola: She became a deputy district attorney in the Los Angeles District Attorney's Office. I also started my career as a deputy attorney in San Mateo County. So that also spoke to me. Also that she was integral in starting the public defender's office. There's actually a building in Los Angeles named after her because she was the person who started the first public defender's office. What she started has helped countless people who otherwise would not have attorneys.

Dunkle: Can you tell us about some notable female attorneys you crossed paths with during your career?

Meola: Yes, Sandra Day O'Connor and Kamala Harris. Sandra Day O’Connor graduated from Stanford Law School and started her career as a volunteer in the San Mateo County District Attorney’s Office.

Dunkle: Wow! She had to start as a volunteer?

Meola: Yeah, because she was a female, they would not pay her. So she started her career there. San Mateo is still a very traditional county with lots of archaic things that need to be changed. But again, that will likely happen in the future.

When Kamala Harris was the Attorney General for California, she actually presented a report about absenteeism in schools, how children lose out when they are absent from school, and how truancy is a huge problem. Harris's report highlighted how important it is for a child to attend school from an early age. And so I attended a seminar she spoke at and was a foot away from her. She's so poised and articulate. She's an inspiration. And you see that now on the national stage. I am looking forward to November and a better result than in 2016.

Dunkle: You mentioned at the beginning of our interview how you didn't have a lot of female role models growing up when you were dreaming of becoming a lawyer, and I'm wondering what it's like for you now to not only see women who are now entering the workplace in larger numbers but also that there is this possibility that a woman lawyer could be President of the United States. What does that feel like to you?

Meola : A range of emotions. I often think that I did not have a lot of female role models as lawyers when I was growing up often. That's the reason why I am part of Women Lawyers of Sacramento, to try to lift up young female attorneys and law students. In my firm I make sure they have the opportunities that they need, and giving them the guidance and the support that they need to be successful.

In addition, a few times when I’m on a hiring committee and we're considering a candidate (not at my firm), if a female candidate has children, a male lawyer says perhaps the person should stay home with their kids. At that moment, I said that I didn’t think that it was an appropriate thing for us to consider. I disagree 100 percent. We all make choices, and we can't judge each other for choices. This is just an example of how sexism continues to happen today, and we have to speak up.

Circling back around to Vice President Harris, when she says we have to fight for freedom, we have to fight continuously to make sure that we are recognized, valued, and respected as the persons that we are, you know, in addition to being female, not despite being female, but in addition to being female.

Upcoming Events

This Sunday!

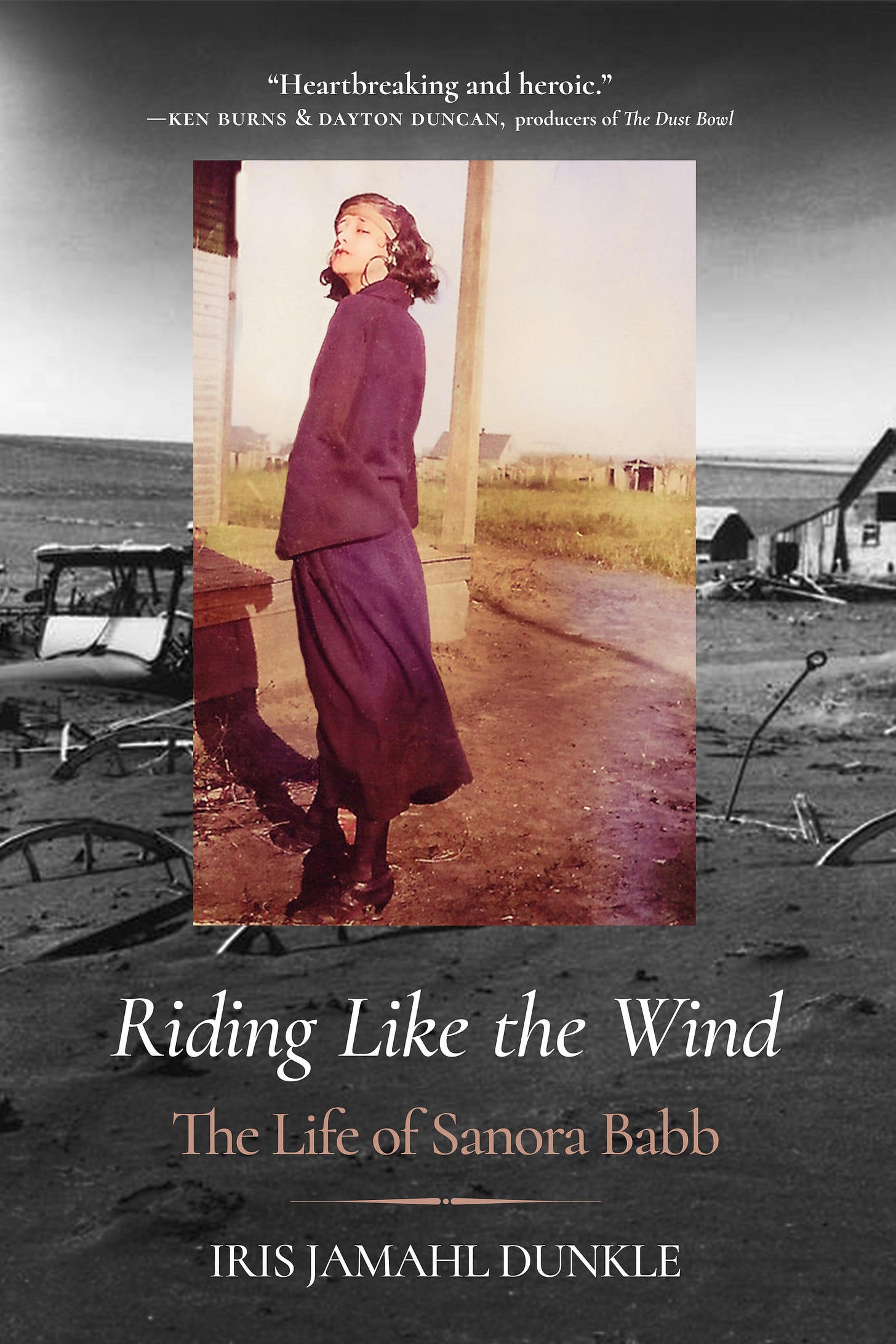

August 25, Books and Books, Coral Gables, FL - An Afternoon with Nicole Callihan, Suzanne Frischkorn & Iris Jamahl Dunkle

Riding Like the Wind: The Life of Sanora Babb Launch!

October

October 2-5 58th Western Literature Association Conference in Tucson, Arizona

October 15 - Vromen’s Bookstore in Pasadena, CA - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in Conversation with The Lost Ladies of Lit Co-hosts Kim Askew and Amy Helmes,

October 16 - 6:00 PM - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at Bookmine in Napa.

October 18 - 7:00 PM Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at Copperfield’s Santa Rosa, CA - Register here.

October 23 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle reads at Readers’ Books in Sonoma, CA

October 30 - Iris Jamahl Dunkle in conversation with Harry Stecopoulos at Prairie Lights Bookstore, Iowa City, IA

November

November 1 - 6:00 PM 7:30 PM - Catamaran Lit Chat with Iris Jamahl Dunkle - Catamaran Literary Reader - 1050 River St., Studio 118 Santa Cruz, CA 95060

More dates coming soon!

I have had jury duty in that courthouse named after her on multiple occasions and never thought to question who she was. Thank you for this article, so fascinating... "I'm speaking... and so are my petticoats." LOL