Finding Lost Voices: Amy Lowell, Sylvia Plath and the Brontë Sisters: Part 2 - A Visit to New England

A weekly email that brings back the voices of those who have been forgotten or misremembered

I can’t stop thinking about those blue flowers I saw blooming on Plath’s grave when I visited it in Heptonstall in England. The ones filled with fat bees, regardless of how much rain poured down. I saw the same flowers today, in California, where I am finally writing all of this down. But there were no bees to be found in this stateside version. The plant is called borage. It’s also known as starflower and the bee bush. Seeing the plant again brought my journey vividly back to me.

This post is the second of two posts. (If you missed the first part of this essay, you can read it here.)

After leaving Heptonstall, I traveled to London and New York, where I caught a train to Boston. I was in Boston to attend the Massachusetts Poetry Festival, where I was on a panel called “Sylvia Plath, Radical New Directions.”

The day felt like an adventure before it began; our faces showed it in the selfies we took before leaving my friend Anna’s home to pick up Emily Van Duyne from the airport. Emily is an expert on Plath (see her incredible book Loving Sylvia Plath for evidence of this expertise), so having her with us was vital.

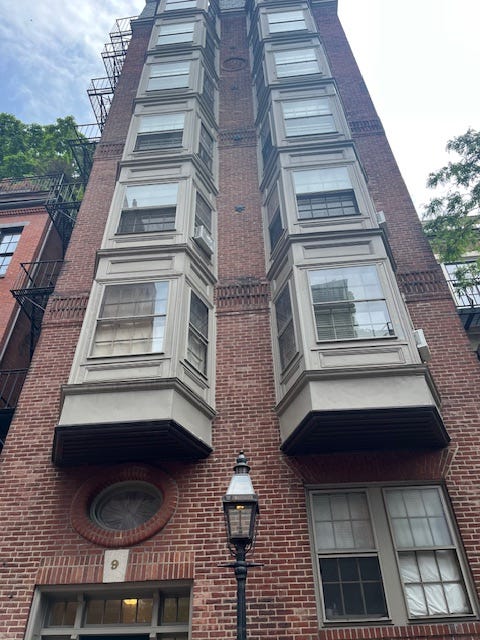

Our first stop was Plath’s home in Beacon Hill, 9 Willow Street, where she and Ted Hughes lived in 1958. We pulled up to the apartment complex on the narrow cobbled street and looked at the seven-story building in front of us. Emily explained that Plath and Hughes had lived in an apartment on the sixth floor. In Beacon Hill, tourists were milling around us, but they weren’t looking for the same ghost. We looked up and saw the windows bulging out like a set of eyes staring back down at us. Joy (who is fearless) tried to get into the building through the front door, but couldn’t. Instead, we all walked behind the building and stared at the giant ash tree that grew in view of the sixth-floor windows. We wondered if Plath had looked out at the same tree. Emily remembered a passage from Plath’s diaries where she mentions brushing snow off a statue in a park near her house, so we walked to the end of the block and found the park, and in it, almost buried behind trees, was a small stone figure hidden behind a lichen-covered fence. Each thing we found felt like a treasure. A hidden artifact that would help us make more sense of Plath’s life.

Satisfied with what we’d seen, we piled back into the car, this time en route to Boston University, where in the winter of 1959, Plath audited a workshop with Anne Sexton taught by Robert Lowell. Stories abound from their time in this class, including the anecdote that Sexton used to take off one of her high heels to use as an ashtray during the workshop, and that the two of them would go get martinis after class at The Ritz with fellow workshopper George Starbuck.

Anna had once taught in this building, so we had no trouble finding it and it was open, so we walked right up to the second floor and found the famed room 222. The large windows in the small room faced the street. There was a student in the room (to whom we apologized), and a Sara Teasdale poem written in chalk on the chalkboard:

“I Am Not Yours”

I am not yours, not lost in you,

Not lost, although I long to be

Lost as a candle lit at noon,

Lost as a snowflake in the sea.

You love me, and I find you still

A spirit beautiful and bright,

Yet I am I, who long to be

Lost as a light is lost in light.

Oh plunge me deep in love—put out

My senses, leave me deaf and blind,

Swept by the tempest of your love,

A taper in a rushing wind.

Plath’s childhood home is found at 26 Elmwood Rd. in the wealthy suburb of Wellesley. It’s a modest house, set back from the road on a wide lawn. When we found it, the four of us paced around it like paparazzi before Joy—again the brave one—walked up to the front door and asked if we could come in. The owners were hesitant, but we were persuasive, and soon, they led us through the dining room and kitchen and down the stairs to the basement. We were led to the crawl space where Plath had once tried to commit suicide when she was twenty years old. An air of solemnity fell heavy over us as we stood looking at the dark mouth that spoke of no choice other than swallowing a bottle of pills and sealing oneself into that grave-like space. The crawl space was directly below the kitchen, so it makes sense that Plath’s brother, Warren, would have heard his sister moaning when she came to—he would have been directly above her.

When we exited the house, we were all changed in some way as if we’d finally absorbed the cost; the cause of what had happened to a twenty-year-old girl who’d been given electroshock treatments without any sedative or muscle relaxant. Who had essentially been tortured and made to feel that her understanding of the world was wrong. It’s not surprising that she felt she was being punished. She made that choice—to crawl into a grave of her own making to save her family the cost and humiliation of having a daughter who was deemed crazy.

On the way back, we almost didn’t stop at Amy Lowell’s home, Sevenels, in Brookline, MA. It was rush hour, we needed to catch the commuter train to Salem. But, I’m so glad we did.

Though I’ve been studying Lowell for twenty-five years, I had never been inside the thick-columned mansion where she spent her childhood and later her adult life. When we drove up, the gravel crunched under the tires. The rest of the day had made me fearless. So as soon as the car stopped, I walked right up to the front door and knocked. When a woman answered, I pleaded my case: I’m an Amy Lowell scholar, I’m dying to see the inside of her home—would she be so kind as to let us in? She thought about it for a moment, got her husband, and then he ushered us in.

Writing about how I felt walking into a home I had only seen in old photographs is difficult. It was as if time had become fluid—had boomeranged me back to the past. The handful of black-and-white photos I’d studied for years blended with what I now saw in front of me.

We first entered the library—a room that had been Lowell’s pride and joy. What was once a dark, mahogany-paneled room was now bright white and light-filled. Lowell had the library constructed as a flex, to hold many of the 50,000 books and literary artifacts she had collected in her lifetime and to have a place to entertain her guests after dinner. In the room, the children who now live in the house ran up to me with a framed document titled: “Residence of Amy Lowell, Panel Board #1”—a note indicating, “Fuses at side Miss Lowell’s Lamp in Library.” It was such an ordinary document, but just seeing Lowell’s name on it filled me with joy.

The family also brought out copies of photographs of the old house. Upon her death, Lowell donated her entire library (both the physical space and the books themselves) to Harvard, but they refused. Instead, they cherry-picked the items they wanted. Because of this, there is no complete record—no list—of all the books Lowell had in her library.

Some of the ceilings throughout the house were still intact, while others had been lost. But the feel of the house remained. Each room we walked through straddled the line between past and present.

I had just spent a day in London at Amy Lowell and Her Imagist Networks, a symposium on Lowell’s work, thinking about how she used poetics of weaponry in descriptions of gardens as a way of reclaiming feminine power, and how her poem “In a Tulip Garden” later influenced Plath’s “Tulips” in Bryony Aitchison’s paper, “Virile Imagism and the Natural World in Amy Lowell’s Sword Blades and Poppyseed” and Hannah Roche’s paper “Plath, Hughes, and Amy Lowell": Relations and Reflections.” And so the day, and the way I had seen the physical places where both Plath and Lowell had lived just miles apart, was uncanny.

So much of Lowell’s influence on other poets like Plath has been erased, mostly because so much of her life has been erased. She was raised at Sevenels, once a spacious 9½-acre estate. When she lived there, 18 full-time staff members kept the mansion running. In that library, Lowell kept a safe containing treasures she had assembled through a lifetime of collecting rare books begun at age eighteen, including Emily Brontë’s Bible, Anne Brontë’s proto-feminist novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and nine miniature autograph manuscripts by Charlotte Brontë.

Just a few days earlier, I peered into another, even older house, the Brontë Parsonage in West Yorkshire, where these three sisters lived in the 1820s. The house, which sits on the edge of a graveyard, above the steep, cobbled streets of Haworth, has been made into a museum and contains the recreated scene of the Brontës' dining room, where each sister likely wrote their books. It had been so strange to see these writers and the world they inhabited brought back to life so many years later. How different it felt to see the moors that surrounded the house—those I had only imagined in the Brontës’ novels. I suddenly understood how isolated Jane Eyre had been when she ran away from Thornfield Hall or how violent the windswept and stormy moors found in Wuthering Heights had been when Heathcliff wandered through them. These places were more isolated and dangerous than I had ever imagined. and I would have never understood that unless I had been there, in person, to witness what it felt like to be there.

And now, having walked inside Lowell’s home—having seen the gardens she once used to express her queer love in “Two Speak Together” torn up and divided—to see the house decapitated, rid of the Sky Parlor (the addition Lowell had made to the house, which was her writing studio and the bedroom she shared with her partner Ada Dwyer Russell), I felt the physical presence of her story come alive inside those walls in a way I couldn’t have felt it before. It was touching that the current owners were uncovering some of the house’s original features.

But it’s the dark mouth of erasure and false biographies about Plath and Lowell (and likely the Brontës) that will keep speaking to me long after this day. Prior to this week of travel, I’d walked into the stories of Plath and Lowell through secondary sources. Here, standing on the same ground where their bodies once lived, I was finally starting to see them for who they truly were.

For More Information

To read the First Part of this Column Finding Lost Voices: Amy Lowell, Sylvia Plath and the Brontë Sisters: Part 1 - England

To see photos of the inside of Sevenels as it is today, see https://www.stevenharrisarchitects.com/projects/boston-house

For more information about the life of Sylvia Plath, read Loving Sylvia Plath by Emily Van Duyne

Upcoming Readings

July 26, 1:00 PM - Poetry in the Parks: A Reading with Ada Limón, Nicole Callihan, and Iris Jamahl Dunkle at Armstrong Woods, Guerneville, CA

Iris, I have been absolutely *hooked* reading these 2 essays on your recent travels — thank you so much for bringing us all along with you! 🌻

It was great going along with you on your tours, and you're so fortunate to have been invited in by the current owners. What a hoot! Thanks for sharing.