“When I look outside my window

Many sights to see

And when I look in my window

So many different people to be

That is strange

So strange

You’ve got to pick up every stitch

You’ve got to pick up every stitch

Mmm-hmm, must be the season of the witch

Must be the season of the with.”

–Donovan

For the last ten days, I’ve been on the road researching an article about Amy Lowell’s literary influence on Sylvia Plath. Seeing the places where these two extraordinary women lived changes the way you perceive their lives. This is part one of a two-part post about my trip.

I boarded a red double-decker bus to the London Zoo stop in the Primrose Hill neighborhood. Along the way, the streets were alive with men in red and white striped jerseys singing about their soccer team’s victory. I got off near the Zoo and walked up a block and a half to Fitzroy Road. The sidewalks were filled with people walking their dogs. Maple and Oak trees shaded the sidewalk. I walked under a gray sky to Sylvia Plath’s last home, where she lived on the second floor with her two small children. There is a blue plaque that marks the building as where W.B. Yeats once lived. But nothing that marks her life. Someone else lives inside. I could see their photographs through the window.

I continued on to the end of the block and then turned left to walk to Plath’s earlier home, the one where she’d given birth to her daughter Frieda Rebecca Hughes on April 1, 1960, where she lived with Ted Hughes, where he was living at the time of her death, 3 Chalcot Square. When I arrived at the house, the air smelled like roses. A woman saw me and, as she walked past, shouted accusingly, “Sylvia Plath?” Then she shook her head and kept walking. The house looked out at a quiet, green park across the street. The garden was lush and full of life.

After I left Plath’s homes, on a whim, I took the underground down to the Globe Theater. As I descended to the platform down a long, spiral staircase, I imagined what it must have been like to try and transport two small children down this long stretch during England’s coldest recorded winter when Plath lived in this neighborhood. The Globe Theater no longer resides in its original site. When I walked into the reconstruction down the street, I asked if I could go on a tour. They said that wasn’t possible because they were in performance, but if I’d like to buy a standing ticket, I could go in and look around. I said yes, bought a ticket and walked into the open air theater. The cast was performing Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible.” I stayed to watch the scene where a woman is accused of being a witch and she is taken into custody. When you are in the standing area at the Globe, the actors walk on and off the stage past you. So when they took the woman away, I was standing next to her. Shackled, she was shoved into a small cart and wheeled away. The play is set in Salem, Massachusetts — a city where I will travel in just a few days. Which felt like so much more than a coincidence - more like a sign. Here I was researching women who had been ostracized for being different, and now I see the “crying out” performed before me, set in the raw Massachusetts winter, where people were known for minding their own business.

“We are edged with mist. We make an insubstantial territory.” — Virginia Woolf The Waves

The next morning, I took one train north to Leeds and transferred to another to Hebden Bridge. As soon as you exit the train, you are told that this has been a literary area for over 500 years. You can catch a green Brontë bus to visit the Brontë Parsonage and museum a few miles away in Haworth. I walked past the canal filled with houseboats and through the town of Hebden Bridge. I found the cobbled path up to Heptonstall on the other side of an arched stone bridge. It was very steep. I dragged my book-laden suitcase up the mile-long ascent. At the top, drenched in sweat, I met Susannah Demko in a tea shop (the only tea shop in town). After a cup of tea and a scone, she walked with me to the graveyard where Sylvia Plath is buried.

Heptonstall is a small village of about 1400 people. First recorded as a town in 1274, the name means the stall or stable in the rose-hip valley. The town was once the center of hand-loom weaving, and because of this, all of the homes have first-floor windows to maximize light.

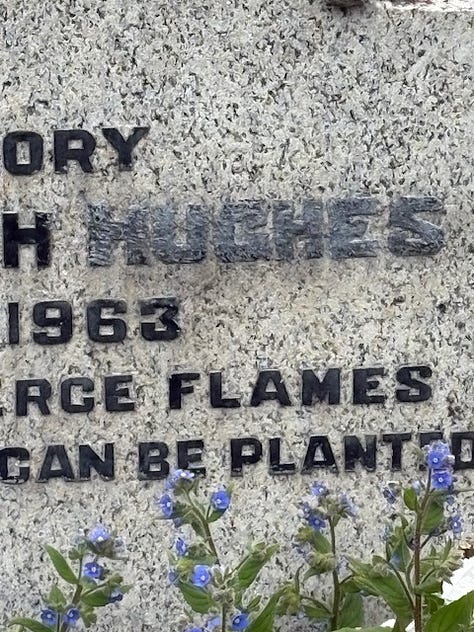

We walked through the ancient graveyard, past the ruins of an earlier church founded in 1260, and whose stone walls still rose against the grey sky. Then we walked around the Methodist church whose foundational stone was laid following John Wellsley’s visit in 1764. Susannah points out a headstone for Esther Greenwood, who she thinks may have been the inspiration for Plath’s protagonist in The Bell Jar. Then we enter the graveyard extension on the southwest side of the church. It’s a wide field, parts of which have been marked off to become a garden of wildflowers. Susannah leads me up the center and to the right to Plath’s grave. Her headstone peaks out from a bed of blue-flowered plants that have grown rampant and taken over her plot. Even in the wet air, fat bees swarm their blooms. The headstone is light grey and on it are inscribed the words:

In Memory

Sylvia Plath Hughes (Hughes has been scratched out)

1932 - 1963

Even admidst fierce flames

the golden lotus can be planted.

The quotation Hughes chose to place on Plath’s grave when he finally placed the stone eight years after he buried her is from the classic Chinese novel, Monkey: Journey to the West by Wu Cheng'en. The complete quotation reads: "Even in the midst of fierce flames the Golden Lotus may be planted, the five elements compounded and transposed, and put to new use. When that is done, be which you please, Buddha or Immortal."

Around her grave, Plath’s admirers have left flowers, roses, and tulips. There is a cup full of pens, rocks, and silver bracelets. Later that afternoon, Susannah takes me to her home and shows me her treasure: two watches that once belonged to Plath. She encourages me to put one on. I do and feel the residue on my wrist long after I take it off. On her bookshelves, she displays a framed series of photographs taken at Beacon House (Ted Hughes’ parents’ house just above Heptonstall). When I walk back to the cottage I’m staying at, the town feels like a small nautilus shell. I want to unwind more to try and better understand it.

The next day, I wake up early because the sun comes up before 5 AM. I couldn’t go back to sleep, so I set out for a walk back to Plath’s grave in the light rain. A cold wind pushed through. No one else was out, just a black and white cat that looked me over and then ran away. The grave was just as I’d seen it the night before. The blue flowers were now wet with rain, but still the bees persisted, humming around the blossoms.

After I left her grave, I walked to the pub “The Cross Inn” where Hughes had held Plath’s funeral after he buried her. At the time, her mother didn’t even know she was dead. I walked out of town on the cobbled road until I came upon a sign marked Lumb Bank - the former mill owner’s house that Hughes bought in 1969, now a writers’ center. I walked down the steep path to the house and back through the forest into town.

Plath first visited Heptonstall in August 1956, when she met Hughes’ parents for the first time and posed for the photographs at their home that Susannah kept on her bookshelf.

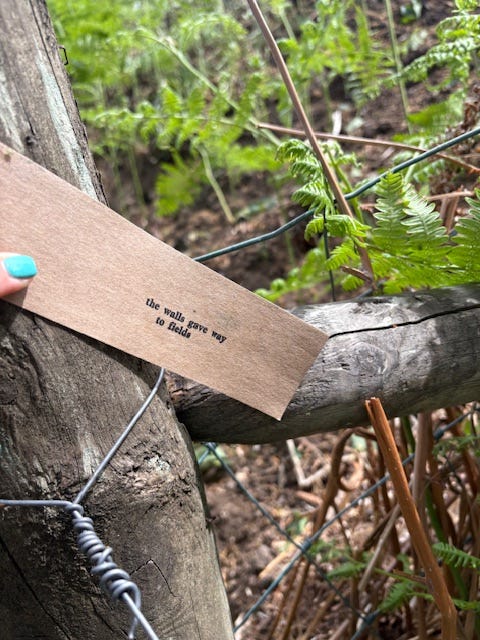

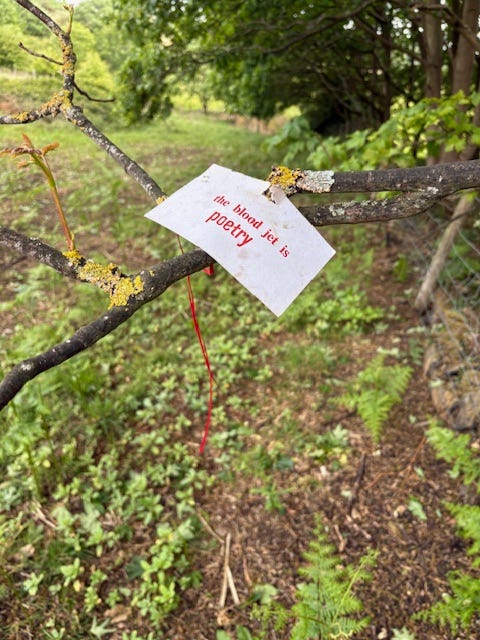

Later that morning, I met David Mullin, and he took me to Hughes’ childhood home in the old mill town of Mytholmroyd. The town’s name dates back to the Vikings who once lived here (meaning, the farm where two rivers meet). Hughes grew up on Aspinall Street in the shadow of a Methodist church that is no longer there, with a view of Scout Rock on the far-off hillside. David took me down the path that Hughes and his brother would have taken to go to school and up to the bluff where he and his brother once flew kites. All around this landscape, David and the Plath scholar Emily Van Duyne (who’d visited here just a few weeks before me) had left cardstock cards printed with words from Plath’s poems. They were pinned to fence posts, dangling from trees, and hidden under rocks as if they were trying to reclaim the narrative.

We walked along the canal that borders Mytholmroyd then we drove up the hill to see Beacon House. Hughes’ parents moved to this house while he was attending Cambridge, and David points to the back stone wall where those photographs of Plath and Hughes’ family were taken. Next to Beacon House is Crown Point, two benches on an ancient trash heap where the earth is dark, rich, and filled with scraps of ancient pottery. We walked down the slope to Lumb Bank, and I’m surprised by how close together Hughes’ home is to his parents’. Hughes had wanted to buy this house while Plath was still alive, but she didn’t want to live there. She never wanted to stay in Heptonstall long.

David drove me over the moor to the Brontë Parsonage in Haworth. I toured the house and bought a copy of Elizabeth Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë, which was first published in 1857. Gaskell was a friend of Brontë’s and therefore wrote an “official” biography. Each room of the house was recreated as they were when the Brontë family lived there. Carved on a stone at the back of the field was this poem:

“These dark sober clothes are my disguise. No, I was not preparing for an early death, yours or mine. You got me all wrong, all the time. But sisters, I’ll have the last word, write the last line. I am still at sea—but I can do some good in this world. I will right the wrong. I am still young and the moor’s winds hit my light-dark hair. I am still here when the sun goes up and here when the moon drops down. I do not now stand alone.”

The stone is called the Anne Brontë stone, and the words carved into it are a poem by Jackie Kay as part of the Brontë Stone Project. In 2018, writer and musician Kate Bush, poet Carol Ann Duffy, poet and novelist Jackie Kay, and novelist Jeanette Winterson came together to celebrate the literary legacy of the Brontë sisters. Each sister is remembered by a stone set in the enigmatic landscape immortalized in Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights.

When I leave the valley on a train to London, I leave changed. The place has seeped into me, making me look and understand parts of the narrative I’d never understood.

(Stay tuned for Part 2 about my the continuation of my trip in Boston later this week).

I just thought I will read the title, then I thought I'll read the first paragraph and then I could not stop. Well done!

What a fascinating journey!!! Can’t wait to hear more.